‘T

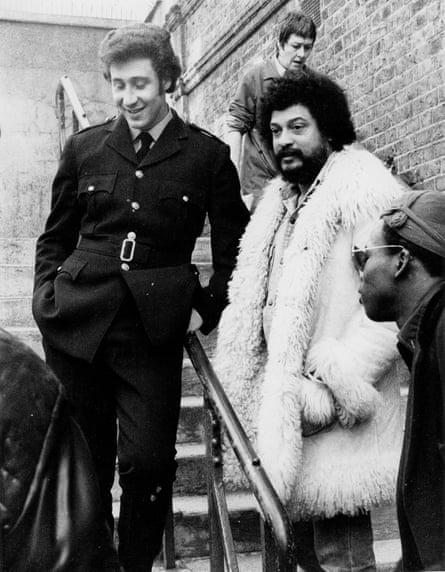

Indra Ové, an actor whose father was a film-maker, recalls the constant presence of police at their door. They were searching for her father, Horace, whom they believed was stirring up violence with his camera. However, Ové explains that her father was primarily capturing the discrimination and mistreatment faced by black people in 1960s Britain and beyond. His most renowned work, Pressure (1975), depicted the growing tensions and lasting impact on the black community’s physical and mental wellbeing.

When I reached out to them, my family, friends, and colleagues from Britain, Nigeria, and the US were all eager to express the brilliance of Horace Ové, who is now the focus of a major exhibition at the BFI in London. As black teenagers, my siblings and I were amazed while watching Pressure. It was the first time we saw people like ourselves on the big screen. Horace’s son, artist Zak Ové, shared this sentiment as he also grew up feeling confused and disconnected from his roots. He explained, “Your parents would talk about the tropics, palm trees, and beautiful beaches – things you had no connection to while growing up in council estates and being seen only as immigrants who should return home.”

Originally titled The Immigrant, Pressure was co-written by Sam Selvon, author of The Lonely Londoners. The film tells the story of a black teenager living in 1970s London, the son of Trinidadian parents, struggling with his identity and caught between two cultures. The film’s release was timely, as the following summer saw clashes between black youth and police at the Notting Hill Carnival. However, the film was not well-received and was effectively banned by the British Film Institute (BFI). According to Margaret Busby, this was due to fears that the film would incite further unrest after the riots. Busby also notes that Ové’s films depict interracial and intergenerational scenes of black lives in a way that had never been seen before.

According to civil rights advocate Gus John, Horace Ové rose to prominence as a filmmaker and documentarian during a time when it was crucial to establish our presence in British art and culture as a form of resistance against racism. John believes that the 1970s and 1980s were a period of great significance, with philosophers, artists, and activists coming together in a similar way to the 1920s Harlem Renaissance, using the arts as a means to achieve equal rights through copyright laws. John states that Ové’s film Pressure served as a powerful tool for the nation to reflect on its flaws and confront them head-on.

Lyndsey Barrett, a Jamaican writer who worked with Ové in the early stages, praises his film “Pressure” for its unique and revealing approach. She notes that Ové had a talent for helping actors truly embody their characters rather than simply reciting lines. His approach was not pretentiously intellectual, but rather reflected his roots and upbringing in Trinidad.

In 1936, Ové was born in the Belmont region of Port of Spain, Trinidad. According to director and actor Burt Caesar, this was a stroke of luck as the small Caribbean island rejected narrow-mindedness. Belmont, in particular, provided a fertile environment for the young Ové’s creative mind to flourish. Caesar describes it as an open-minded, diverse and vibrant community with a reputation for being bohemian.

Ové arrived in Britain in 1959 with a goal of becoming an artist. He held several part-time jobs, including a hospital porter, mortuary assistant, and working on a North Sea fishing trawler, before landing a role as a featured extra in the film Cleopatra (1963). While filming in Rome, Ové was influenced by the spirit of La Dolce Vita and the works of Federico Fellini. French films also had a significant impact on him, with Barrett noting that he was particularly inspired by the New Wave movement and encouraged improvisation with his actors. He used a naturalistic approach similar to Jean-Paul Belmondo’s coaching style, even with non-professional cast members.

After coming back from Rome in the 1960s, Ové attended the London School of Film Technique (now known as London Film School). His initial short films, highly praised by artist and director John Akomfrah, had a dreamlike quality that evoked what George Lamming referred to as “a sense of unfamiliarity”. According to Akomfrah, these shorts captured the mystery of migration and settling in a new place, where everything feels foreign. As time passes, even the newcomers themselves become unfamiliar. The films showcased the emotional themes that would now be described as Afrofuturism.

Ové’s appearance in the 1973 satirical film Black Safari marked a departure from the Afrofuturistic trend. The film follows a group of explorers as they journey from Africa to the “primitive” center of Britain. In contrast to the typical white European adventurer stories popular in British media, Ové’s Trinidadian background shines through with a unique and playful twist. Along their voyage to Wigan, the African adventurers rename British plants and animals after esteemed African leaders.

African rulers and leaders discovered their contemporary Carnival counterparts in the streets of Chapeltown in Leeds, Notting Hill in London, and Port of Spain. Their flamboyant costumes, created by revolutionary costume makers using glue guns, were showcased in Ové’s 1973 film King Carnival. During this time, Notting Hill, particularly Ladbroke Grove, was the epicenter of Black political activity in London. Horace Ové was a prominent figure in this community, often engaging in debates at the Mangrove cafe. This cafe and club served as a gathering place for political discussions and a symbol of racial pride, as depicted in Steve McQueen’s recent Small Axe series. However, Ové had already documented the significance of the Mangrove in his 1973 film co-produced with The Mangrove Nine.

Horace Ové, a filmmaker, was always aware of his collaborators’ concerns and was able to bring out genuine and unfiltered performances from them. In one notable scene in Pressure, the police unexpectedly disrupt a Black Power gathering. Albert Bailey, who landed his first job as an electrician on the film, recalls how Ové kept the details of the scene a secret from the cast. The actors were so immersed in their roles that they thought it was a real raid and had to be stopped by Ové from reacting too forcefully towards the extras playing the police officers.

Ové’s later works primarily consisted of television dramas that maintained the same sense of urgency and pacing in their storytelling. One notable example is the BBC Play for Today production A Hole in Babylon (1979), which may have appeared to expose a failed burglary at an Italian restaurant, but actually delved into the ideals driving the emerging Black Power Movement. Despite their misguided actions, the main characters saw the Spaghetti House siege (as it was later known) as a revolutionary response to the exploitation of empire and colonialism. The proceeds from the heist were intended to support black education. “If Ové had not been black, his film would have been praised,” says Akomfrah. “His mastery of drama and documentary elements was ahead of his peers, even as it reflected the new realism seen in Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966).”

Ignore the newsletter advertisement.

after newsletter promotion

Each person interviewed expresses great enthusiasm for the filmmaker, with Zak Ové in particular speaking passionately about one of his father’s signature techniques: using long shots to allow scenes to unfold and draw the audience into the moment. Akomfrah also shares this sentiment, noting that Ové’s focus was not on performances but on creating an immersive environment within the frame. This approach gives the viewer the freedom to observe and engage with the action. In his film “A Hole in Babylon,” we are drawn into the drama and become a part of it. This immediacy is also evident in Ové’s documentary “Dabbawallahs” (1985), where he empathetically captures the perspective of Mumbai’s dabbawalla porters as they rush through the streets with their lunchbox-laden trolleys. It is a remarkably compassionate portrayal.

All the people I talked to confirm the friendly, welcoming, and mischievous atmosphere that Ové created on his film sets. Despite the serious topics he tackled, his reputation for playfulness is surprising. However, the humor always had a sharp edge to it, especially in Playing Away (1987), a comedic drama written by Caryl Phillips about a cricket team from South London who compete in a tournament in the English countryside. Phillips, who was traveling by train between Princeton and NYC, explains, “The tone of that film was very different from contemporary dramas that focus on issues and conflicts.” He adds that “Horace fully understood the subtle complexities of British society.” Playing Away highlighted the commonalities, such as social class, that were more important than race.

He was a charismatic man who inspired collaborators. Upon hearing about James Baldwin’s appearance at the West Indian Student Centre in London’s Earls Court in 1963, he quickly gathered a group and went to the venue. There, Ové impressed Baldwin and Dick Gregory enough to gain permission to film and capture the intense intellectual discussions that echoed throughout the building that evening. The resulting footage became the film confidently titled Baldwin’s Nigger, a nod to a phrase used by Baldwin himself during the debate and documentary. The writer and civil rights activist explained that he was a descendant of slaves owned by a man named Baldwin, who would refer to them with that derogatory term.

According to Gus John, Horace Ové had a significant impact and was highly influential, much like how Wole Soyinka and Fela Kuti were to Nigerians. Similarly, Ové could be compared to James Baldwin’s representation of African Americans. People often described him as “fearless” and “generous.” Filmmaker Akomfrah remembers how Ové instilled trust in the black community and made them feel that working together towards a common goal was valid. His influence has left a lasting impression on multiple generations of black artists. As one person puts it, “After meeting Horace, I am not afraid of anything.”

Zak Ové pays homage to his father by stating that he broke down barriers that sought to limit black artists to spaces focused on defending themselves against racism. These barriers also attempted to pigeonhole them into solely identifying with their race as a subject. “He opened the door for us to envision ourselves beyond these limitations and soar freely.”

Source: theguardian.com