The year is 2008 and China is opening to the world. Announcements about the summer Olympics in Beijing are blaring out from loudspeakers across the country, stirring up national pride about an event that underscores China’s confidence in the 21st century. But in a far-flung corner of north-west China, on the edge of the Gobi desert, the sparkle from the capital has faded into a translucent dust, coating everything in a declining industrial town with a bleak, grey haze.

It is here that Black Dog’s central human character, Lang, freshly released from prison, finds himself, as he returns to his barren home town to reconcile with his ailing father and former neighbours, who regard him with suspicion.

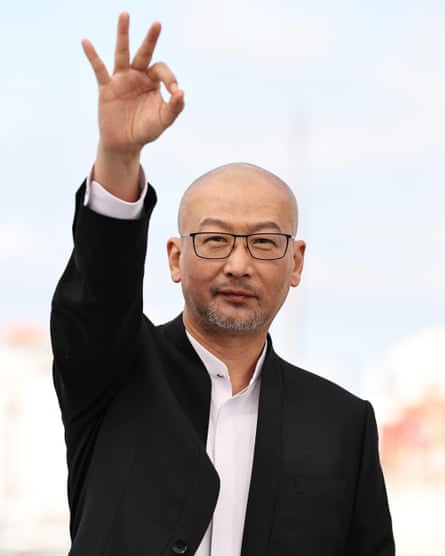

“For anyone who understands China, looking at the past two or three decades, 2008 was a turning point,” says Guan Hu, the director of the feted new Chinese film Black Dog, which chronicles Lang’s attempt to build a fresh start just as China is also reinventing itself. Guan is referring to the “unparalleled pride” of the Olympics, but also the “immense sorrow” of the Wenchuan earthquake, which struck in May of that year, killing nearly 70,000 people. For Guan, there is power in writing about ordinary people in such an “iconic year”.

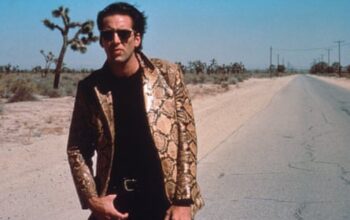

The film’s title comes from Xin, a stray black whippet that Lang, played by an impressively rugged Eddie Peng, befriends after he is assigned to a local dog patrol, tasked with rounding up stray hounds ahead of the Beijing Games. The friendship between the largely mute Lang and the unruly but loyal pooch grows as Lang struggles to find his place in a town that feels increasingly abandoned. Several scenes include dusty concrete buildings emblazoned with the character 拆, or chai, a tagging used by authorities in China to earmark buildings for demolition.

Guan says that he always wanted to make a film about humans and dogs, not least because of his love for his pet German shepherds. “Individual human life seems incredibly small and insignificant in the face of nature. But when you focus on that individual life itself, the life of an ordinary person is immensely significant. So, it’s a story of two extremes. We wanted to explore the animalistic nature of humans,” he says.

Black Dog, a moody, sprawling, western-meets-noir with a dash of social commentary, is a departure from the 56-year-old director’s previous works. His two most recent blockbusters, The Eight Hundred and The Sacrifice, were more sabre-rattling portrayals of Chinese military might than meditations on China’s left-behind towns. But after netting more than $484m and $173m at the global box office respectively, the two films put Guan, already an important figure in the so-called “sixth generation” of Chinese film directors who came of age in the early 1990s, in good stead to make a more edgy feature. Black Dog was the first film produced by the production company Seventh Art Pictures that Guan co-founded with his wife, Liang Jing.

For a film to be released domestically in China, it must first obtain a “dragon seal” from the government-run China Film Administration, a lengthy and murky process which involves strict content reviews. China’s film censorship has tightened in recent years, with the authorities cracking down on unauthorised screenings. But Liang says that the process of obtaining a dragon seal for Black Dog was smooth. “We felt quite lucky,” she says.

It hasn’t just pleased the censors. Black Dog has also received rave reviews, winning the top prize in Cannes film festival’s Un Certain Regard section this year.

As countless other actors have discovered, the dog is just as compelling as the human star. The entrancing opening scene features hundreds of stray dogs galloping across a flinty, arid shrubland, shot as a haunting, washed out panorama by Gao Weizhe, the director of photography who previously worked with Guan on The Sacrifice. But it is Xin, the stray whippet, who comes to the fore as Lang’s newfound best friend.

“The biggest challenge was patience,” says Guan, of the experience of working with a canine cast. “Even if we rehearsed for a long time, and things were going well, once we were on set the animals could get tired or annoyed, and may not perform as well as we imagined, or even worse than in training … Everything else, like the weather, was manageable”.

Befitting a gritty, raw film about the challenges of real life, Guan says that he didn’t use CGI for any of the scenes. That includes a particularly impressive moment where Xin jumps through a solid glass window to intervene in one of the many fist-fights that Lang finds himself embroiled in as he struggles to find his place in his old town.

For Guan, the film is as much about communication as it is about companionship. Black Dog is his attempt to portray the “indescribable” communication between man and dog “that doesn’t require words”. And in Black Dog, Guan says, “the dog isn’t just a pet. He acts as a character – an extension of [Lang’s] own lonely soul.”

Additional research by Chi Hui Lin

Source: theguardian.com