F

For those who believed that David Fincher’s previous film, Mank, marked the start of a more sophisticated phase for the director, his latest work will come as a surprise. While Mank focused on the writing of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane and was a lavish and substantial homage to old Hollywood (earning 10 Oscar nominations and 2 wins), his new movie, The Killer, is a gritty and action-packed hitman thriller based on a comic book. “I will always carry my inner 12-year-old with me and I am proud of that,” he declares.

Fincher appears to be embracing his youth rather than aging, but in a characteristic and controlled Fincher style. During our meeting at a London hotel, he seems to be in a particularly calm state. He appears to be in good health and is filled with humor and vitality, almost as if this is not yet another interview in his 40-year-long career.

Despite being a highly acclaimed and unique movie creator, Fincher does not like being labeled as an “auteur” or an artist. He believes there is a misconception that film directors simply tell others what they want and then retreat to their trailer while the movie is made exactly as they envisioned. In reality, the process involves a lot of hands-on work and is more comparable to playing with puppets and taking care of children or doing plumbing and construction tasks. It is much more physically demanding than most people realize.

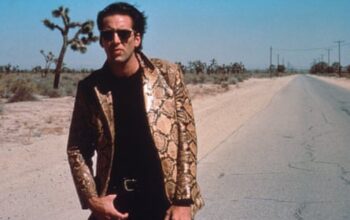

However, when discussing The Killer, he explains, “I didn’t want to approach it too seriously.” He characterizes the movie as a “high-quality B-movie”: concise, captivating, and unexpectedly humorous despite its intense action scenes. Michael Fassbender’s portrayal of a lone assassin is almost comical in his meticulousness, from his deliberately un-Bond-like wardrobe (reminiscent of a German tourist) to his reusable collapsible cup for job assignments, to his selection of Smiths songs on his playlist. But when his carefully crafted plans go awry, he’s forced to break his own rule: “Plan ahead, don’t improvise.”

Could we potentially be seeing some of Fincher’s personal style shine through in this film? He is known for his meticulous attention to detail and lengthy filming process, often doing multiple takes. Fincher himself acknowledges the similarities between his approach to filmmaking and that of the main character in the film. He pays close attention to technical aspects and uses his tools with precision. He was even involved in refining the subtitles, wanting to ensure they accurately reflected the immediacy and subjectivity of the story. Fincher’s ultimate goal was to immerse the audience in the protagonist’s perspective, placing them in his “orbital sockets”.

Was his strict policy of multiple takes loosened for this movie? “Absolutely not,” he answers. “I don’t lower my standards. I cannot change my approach. I strongly believe that our main focus should be spending time in front of the camera with the actors. Anything else is irrelevant.”

The individual speaks highly of Tilda Swinton, particularly for her demanding nighttime scene in the snow. They shot 26 takes of it, which was quite complex, but she was determined and persevered. Despite the freezing temperatures, she was prepared with warming packets in her pockets and was compared to the Michelin woman.

Regarding Fassbender, he has shifted his focus from acting to his “first love”: motor racing. He has participated in the 24-hour Le Mans race for the last two years. Fincher caught him at a fortunate moment: Fassbender had recently viewed Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1967 thriller Le Samouraï. The methodical assassin portrayed by Alain Delon was a clear inspiration for The Killer. According to Fincher, Fassbender expressed to his agent: “We should do something similar.” It appears that Fassbender was well-suited for the role. “We’re discussing someone who is precise and also emotionally receptive,” he explains.

Fincher is aware that the concept of professional killers utilizing sniper rifles to take out targets and escape undetected is unrealistic. The film, The Killer, was based on a French graphic novel series by Alexis “Matz” Nolent, which presented a world that exists outside of mainstream society. Fincher was intrigued by the idea of using technology to disconnect and isolate oneself from others, while still being able to function in society. The main character, played by Fassbender, takes advantage of this digital world to live a life of anonymity, from shopping to banking. However, the appeal of this concept also lies in its ability to provide entertainment, as Fincher states, “I was drawn to the assassin as a means of creating tension.”

As a child, he recalls reading comic books, specifically American Cinematographer when he was 10 years old. This was during the 1970s, before the 1980s revival of comics led by writers like Alan Moore and Frank Miller. Fincher adds that he had already relocated to Hollywood by the time Frank Miller was revolutionizing Batman.

In 1999, he presented his idea for a movie about Spider-Man. Fincher’s version did not include the traditional storyline of being bitten by a radioactive spider, instead focusing on an adult Peter Parker. He jokingly recalls that the studio was not interested in his approach, questioning why he would want to change the origin story. He responded by saying that he found it to be silly and unappealing. Ultimately, the project was given to Sam Raimi.

Fincher’s career has always wavered between highbrow and pulpy. He didn’t go to film school, instead cutting his teeth in music videos, for Madonna (Vogue, Express Yourself), George Michael (Freedom! ’90) and Nine Inch Nails (whose members Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross have been regular Fincher collaborators since 2010’s The Social Network and got an Oscar nod for the Mank score). It gave Fincher his technical knowhow and eye for an arresting image.

After making the switch to feature films, his decision-making has become quite unpredictable, as he often reminds me: “How do you follow Fight Club with Panic Room?” He has also directed the disappointing Alien 3 alongside the darkly brilliant Seven, and the timely tech drama The Social Network alongside a seemingly unnecessary remake of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. He seems to reject the label of “auteur” with his inconsistent choices.

He admits, “I struggle with that because a) I am not invested in it. But b) When I was creating Fight Club, I faced criticism for my choices. And now, with a film like The Killer, people question why I am not sticking to my earlier, more impactful works. It’s a no-win situation for me.”

However, there are consistent patterns in his writing that revolve around troubled white men who are outsiders. These characters are typically depicted as violent in works like The Killer and Fight Club, or deliberately rebellious against societal norms in projects like Mank and The Social Network. In some cases, they even take on the role of serial killers, as seen in Seven, Zodiac, and the Netflix show Mindhunter.

The speaker expresses a personal belief that even popular high school students, such as the quarterback dating the cheerleading queen, feel like outsiders. He compares himself to filmmaker Tim Burton, who sees his character Edward Scissorhands as a unique anomaly. However, the speaker believes that most people can relate to feeling like an outsider, much like Edward Scissorhands.

Fight Club holds significant relevance in today’s understanding of masculinity. Based on Chuck Palahniuk’s 1996 novel, it presents a commentary on the boredom, impending irrelevance, and self-pity of white American men, which seems to have accurately predicted and possibly influenced the current cultural climate. As Tyler Durden, played by Brad Pitt, proclaims to his followers, the film highlights the wasted potential of men and their pursuit of material possessions through unfulfilling jobs.

Fight Club became a key text for a contingent of dissatisfied white men that we might call the “manosphere”: “incels”; neo‑Nazi fitness clubs; the Proud Boys (which the Southern Poverty Law Centre once described as an “‘alt-right’ fight club”); avowed misogynists and male supremacists in the Andrew Tate mould.

Fincher states that he is not accountable for how others interpret his work. He points out that the current reception of Fight Club by the aggrieved manosphere is different from its initial release in 1999 or its popularity on college campuses when it was released on DVD. He acknowledges that language and symbols change over time. However, he acknowledges that the film has become a reference point for the far right. When I mention this, he responds with slight frustration, stating that it is just one of many terms they use.

What are his thoughts on this? “Although it wasn’t intended for them, viewers may see elements reminiscent of a Norman Rockwell painting or Picasso’s Guernica.”

The person is suggesting that it could be a matter of perspective, but Fight Club was clearly capitalizing on this theme of resentful and disempowered masculinity, correct? “I find it hard to believe that there are people who don’t see Tyler Durden as a harmful influence,” he adds. “For those who don’t grasp that, I am at a loss for how to respond or assist them.”

David Fincher often focuses on passionate, independent male characters (and sometimes female, as seen in Gone Girl and The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo) who challenge various systems. In 2011, it appeared that Fincher was rebelling against the Hollywood system he was a part of. He took a break from traditional filmmaking and created original content for the DVD rental company Netflix. This decision ultimately changed the landscape of streaming media, with House of Cards setting the standard for high-quality, star-studded productions and the binge-worthy release strategy of dropping all episodes at once. While streaming platforms thrived, mid-budget Hollywood projects suffered. Did Fincher anticipate this shift in the industry?

He was still in the process of recuperating from the commercial disappointment of Zodiac, as he clarifies: “Zodiac doesn’t have a lot of plot; it’s primarily focused on the characters. What I took away from it was: ‘Perhaps expecting an audience to sit through a three-hour movie without much action is too much to ask.'” He began exploring scripts for projects on the small screen – “not traditional television, but HBO”. In other words, limited series with 10 or 12 episodes, rather than the usual 20 or 30. “I began considering: ‘This could be a fascinating playground to work in.'”

Netflix granted him access to the sandbox, so to speak. He served as an executive producer for House of Cards, which ran for six seasons. He also worked on the FBI serial killer series Mindhunter, acting as an executive producer and directing seven episodes over two seasons. Additionally, his projects Mank and The Killer were created for Netflix. Fincher is involved in producing many other projects for the streaming platform, including the adult animation anthology Love, Death & Robots.

Is he experiencing any guilt for the downfall of cinema?

He chuckles. “No, I don’t think so. But at the very least, I hope we have shown that the barrier between a movie plot and a longer commitment is now lower.”

He maintains that he is not a rebellious outsider, fighting against the system: “There is a lot of talk about me being some kind of insurgent within the organization, but I have never worked with the mindset that I am creating something in opposition to those who are funding it.”

What is Fincher’s next project? The source material for The Killer spans 15 volumes, making a sequel or even a franchise a possibility. When asked about the potential for a sequel, Fincher responds, “One would think so.” However, he also adds, “I’ve stopped trying to predict what people want.” If any of his films warrants a sequel, it would be The Social Network, given the developments with Zuckerberg, Facebook, and Meta. Fincher’s response is elusive: “Aaron Sorkin and I have discussed it, but that’s a complicated matter.”

If he has any idea what his plans are, he is not letting on, but there is every possibility that he doesn’t. “I never know where I’m headed,” he says. “And I like being lost.”

Source: theguardian.com