It has graced tea towels and cushions, mugs and socks, and spawned numerous Instagram accounts and coffee table books galore. Now brutalism, the once-maligned postwar architectural style of chiselled concrete forms, has finally reached Hollywood, in the form of an epic three-and-a-half-hour film that looks set to sweep the Oscars. You would think that architecture fans would be thrilled to have their subject in the limelight for a change. But they are raging.

There is nothing more irritating to enthusiasts than when the mainstream tries to portray their niche world and gets it wrong. And The Brutalist gets an awful lot wrong. Just as Gladiator II recently vexed classicists with its inaccurate portrayal of the emperors and its anachronistic scenes of people reading the newspaper and drinking at cafes (neither of which, apparently, existed at the time), so too has director Brady Corbet riled the architecture world by playing fast and loose with his interpretation of brutalism, the Bauhaus, postwar immigration and the basic process of architecture itself.

While the film world has showered the movie with five-star reviews – praising its heroic ambition, and drooling at the “authenticity” of shooting with hulking 1950s VistaVision cameras – architecture critics have been up in arms. “The Brutalist gets architecture wrong,” declared the Washington Post. It “perpetuates a colossal cliche,” fumed the Financial Times. Three prominent American architecture critics even got together to record a dedicated podcast, titled Why the Brutalist Is a Terrible Movie. For almost an hour, they railed against everything from the stereotypical depiction of the architect as a lone male genius to the Bauhaus-inspired graphic design of the credits, as well as (spoiler alert!) the idea that anyone would design a community centre and chapel based on the form of a Nazi concentration camp. At the screening I attended, one leading figure from the 20th-century heritage movement could barely contain their fury during the (very welcome) half-time intermission: “It’s just utter tosh!”

The film has aroused this much ire because, for all its claims to be fictional, it is so clearly based on a real historical figure: Marcel Lajos Breuer. Like Corbet’s fictional László Tóth (played by a tortured, quivering Adrien Brody), Breuer was a Hungarian-Jewish architect who trained at the Bauhaus in Germany before emigrating to the US, where he became a prominent proponent of brutalism. He and his contemporaries, including Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, all emigrated in 1937 – crucially, before the second world war, not after, as Corbet has it – and built very successful careers, receiving deanships at major universities, and shaped the following century of modern architecture. None had to queue for free bread. Corbet consulted the architectural historian Jean-Louis Cohen, the leading authority on the period, to try to find the tragic figure that he had in mind, but none came to Cohen’s mind because none existed.

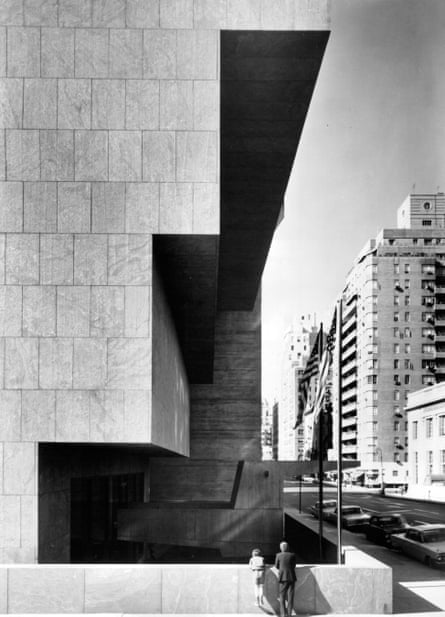

Breuer is best known for designing the former Whitney Museum in New York, which lurches above the street like an inverted ziggurat, and the striking trefoil-shaped Unesco headquarters in Paris. But he first made his name designing curved tubular steel furniture, of a kind practically identical to Tóth’s in the film’s early scenes. “It looks like a tricycle,” the furniture store owner’s wife remarks of the novel bent-steel design in the movie – just as Breuer’s chairs were compared to, and inspired by, bicycle frames at the time.

The similarities don’t stop there. Indeed, one of Breuer’s lesser-known building projects turns out to be the chief inspiration for the film. In the early 1950s, Breuer was commissioned to design a big brutalist church on a hill, just like Tóth – only it was in Minnesota, rather than Pennsylvania, and the clients were Benedictine monks, rather than a millionaire psychopath industrialist. The epic project went through similar agonies to those portrayed in the movie, a fraught process that was meticulously documented in a fascinating book, Marcel Breuer and a Committee of Twelve Plan a Church: A Monastic Memoir, written by Fr Hilary Thimmesh, who served as a junior member of the building committee.

“Our first concern was the novel architecture,” he writes of Breuer’s uncompromising proposal for an angular concrete box, flanked by an abstract bell tower – complete with a cross-shaped void, just like one in the roof of Tóth’s fictional building. “We needed assurance that it was all right to build this odd structure and call it a Catholic church.”

From the very outset of the project, there was suspicion of Breuer who, just like Tóth, had never designed a church, as a Hungarian Jew. “He wasn’t Catholic,” Thimmesh recounts. “His manner was certainly not midwestern.” As in the film’s depiction of a community consultation event, where Tóth shows off a big model of his bulky design to local residents, “biases were noted in the community”, writes Thimmesh, “some against Breuer as a non-Catholic”. Just as the God-fearing people of Pennsylvania in the movie are “worried [the building] is going to ruin the hillside”, and complain that “concrete isn’t very attractive”, so too did the monks of St John fret about the “less than wholehearted support for the plan in the community” and that their Catholic brethren were generally “down on modern architecture”.

Corbet has cited Thimmesh’s book as a key precedent, admitting that “narratively, that was one of the biggest inspirations” – before going on to describe the memoir dismissively as “a pretty dry account of the struggles Breuer went through”. The reality clearly wasn’t spicy enough for his melodramatic intentions. Breuer wasn’t a heroin addict, and the monks didn’t rape him in a quarry. Nor did the real life architect really lose his temper much, beyond the occasional politely worded letter.

after newsletter promotion

In the movie, Brody’s tortured Tóth bristles with single-minded egotism, driven to the edge of sanity by his dogged devotion to the project, choosing to quit and shovel coal rather than see his vision compromised. He regularly erupts with prima-donna fits of screaming when he doesn’t get his way (giving us ample opportunities to learn the Hungarian for “fuck!”), throwing papers around and storming off in blind rage. As his longsuffering wife Erzsébet puts it at one point: “László worships only at the altar of himself.”

By contrast, Breuer was evidently well-versed in navigating the necessary compromises of a building project, as all architects must, while remaining firm in his convictions. At the most heated point during the design of the Minnesota church, when the abbot asked Breuer to sketch out an alternative design, Thimmesh recalls the architect’s measured reaction.

“Breuer responded with something close to emotion,” he writes. “To produce another design, he said, would take time and the same intensity he put into this one. The end result would probably be worse confusion. In choosing a building one does not have the luxury of selecting one of several existing things, he said.” The nuances played out in the decade-long development of this landmark building would have made for a much more interesting story than the film’s hackneyed portrayal of the tempestuous architect-client relationship; but such nuance would be lost on Corbet’s two-dimensional characterisation. Instead, he has his architect spouting meaningless platitudes, such as: “Is there a better description of a cube than that of its construction?” To which his wealthy industrialist client unconvincingly replies: “I find our conversations intellectually stimulating.”

Perhaps the most glaring anachronism is in the film’s bizarre epilogue, set years later at the 1980 Venice Architecture Biennale. Titled Presence of the Past, it was the moment that postmodernism took ascendancy, seeing a colourful parade of architects indulging in cartoonish historical references, embracing wit, humour and knowing pastiche. It was a stage for the new generation’s gleeful dance on the grave of their modernist and brutalist forebears, ushering in a period of buildings like the pink confection of No 1 Poultry in the City of London, and the green-glass Maya temple of the MI6 headquarters in Vauxhall.

Not in Corbet’s world. Instead, he portrays the landmark exhibition as a moment when his fictional, now wheelchair-using Tóth enjoys a heroic retrospective. His stripped-back concrete buildings are evaluated afresh, as “machines with no superfluous parts” – a reappraisal of brutalism that didn’t happen, in reality, until at least two or three decades later.

The architecture world awaits with bated breath the director’s five-hour marathons, The Postmodernist, The Deconstructivist, and The Parametricist – each to be shot with period-appropriate equipment and based on a brief skim through a coffee-table book.

Source: theguardian.com