There are director’s cuts, special editions, redux versions – and then there’s Mr Kneff. Normally, a recut film is the prerogative of a film-maker who feels abused by the studio they worked for, or for whom a streaming platform has given the opportunity to enlarge on their “vision”; but this isn’t quite the case for Steven Soderbergh. In 1991 Soderbergh released Kafka, a tricksy fiction-slash-biopic, which – notoriously – managed to extract nearly all the heat from a film-making career that had got off to a stellar start with the Palme d’Or-winning Sex, Lies and Videotape. Soderbergh, though, is nothing if not a trier, and after years of tinkering, has completed Mr Kneff, a whole new version of Kafka, under a whole new title.

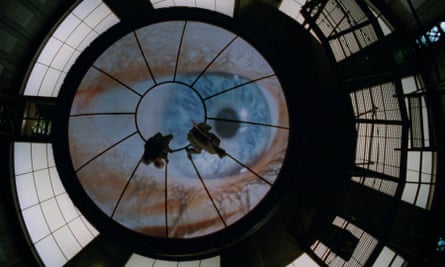

Mr Kneff isn’t exactly the Snyder Cut of literary biopics, in that Soderbergh hasn’t offered up a fan-service retrenchment of something that was apparently denied in the first place. What Soderbergh appears to have done with Mr Kneff is to follow his original inspiration for Kafka – make a film about the 1920s that resembles a film made in the 1920s – to its logical conclusion, as far as is humanly possible. Kafka, if you recall, stars Jeremy Irons as the author, working in an insurance office (as the real Franz Kafka did), getting entangled with a bunch of revolutionary anarchists who are staging bomb attacks in Prague, and finding his way to a mysterious “castle” where a super creepy Ian Holm is leading Brave New World-type experiments on human beings. Filmed in lush black and white (until the final section, where the film switches to a grim, sombre colour palette), and filled with Dutch tilts, pools of shadow and glowering Middle European gothic architecture, Kafka was (and is) a tour de force of silent movie homage. And whether or not he was wearing special makeup, Irons’ resemblance to the Ivor Novello of The Lodger is an eerily brilliant touch.

Except, of course, Kafka was not a silent movie. With Mr Kneff, Soderbergh has gone full UFA and got rid of the dialogue in its entirety (though not the diegetic sounds of footsteps, door-knocks and the like), and added colour tints to much of the black-and-white footage in the approved silent-film manner (orange for daytime scenes, blue for night, etc). The dialogue, much pared down, is now run as subtitles, rather than the individual title cards that pre-sound silents would deploy. It takes a bit of getting used to; the original film was shot with extended talk scenes in mind, while actual silent films would include only the barest bones of dialogue. Hence the particular grammar of silent films with their attenuated dramatic moments, through deploying extended physical reactions around single lines of speech.

But the overall effect on Mr Kneff, once you key into it, is fascinating. For one thing, you become much more sensitive to, and aware of, gesture and glances; this enhances Irons’ performance in particular, whose Charles Ryder-esque world-weariness is transformed into a nervy, twitching creature whose emotional fragility is much more readily apparent. The physicality of Kafka’s comic-sinister officemates Oscar and Ludwig (played by Simon McBurney and, amazingly, Keith Allen) is far more pointed, too. And of course you are much more aware of the camera moves as Irons lopes around the Prague night.

This is all relevant because 2024 is the centenary of Kafka’s death (aged 40, starving to death as a result of tuberculosis), and Mr Kneff will have its first ever UK showing this week at the Ultimate Picture Palace in Oxford, as part of a season of Kafka films that I have helped organise. The allure of Kafka for film-makers is not hard to understand; his visions of the grotesque and surreal are so concretely imagined that they transmit themselves to the reader like a film themselves. Directors such as David Lynch, Terry Gilliam and David Cronenberg have incorporated Kafka’s disconcerting, alienating tropes into their own work to brilliant effect, while others – Orson Welles, Michael Haneke, Agnieszka Holland, Soderbergh himself – are clearly drawn to the siren call of Kafka’s actual life and work.

One of the more fascinating elements of the Kafka film canon, however, is much less well-known: a short film adaptation of The Metamorphosis, called K, directed by Lorenza Mazzetti. Made in 1952, K was only the second ever of all the hundreds of film adaptations of Kafka’s work – an amazing fact in itself – and Mazzetti would go on to achieve a brief moment of renown as the director of Together, one of the three original films in the Free Cinema movement (along with Lindsay Anderson’s O Dreamland and Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson’s Momma Don’t Allow). Haunted by a horrendous childhood experience during the second world war, in which her cousins and aunt were shot dead by German soldiers while she and her sister were living with them, Mazzetti found herself irresistibly drawn to Kafka – in the 1940s a still little-known chronicler of disaffection and isolation – and after wangling a place at the Slade art school at London university, basically pinched camera equipment from a cupboard belonging to the University of London film society. The resulting film is far from polished: it’s the kind of sticky-taped-together effort you wouldn’t be surprised that a penniless art student with zero access to professional facilities or crew of any kind would put together. But K has an undeniable confidence and bravura about it that marked Mazzetti out for bigger things.

Source: theguardian.com