One day in the middle of the afternoon, I got a phone call. On the other end of the line, I heard the name and the voice of the director who would change my life: Francis Ford Coppola. First, he told me he was going to be directing The Godfather. I thought he might be fantasising. What was he talking about? How did they give him The Godfather?

I had read Mario Puzo’s novel, which had become a big hit; it was a huge deal for anyone to be involved with it. But when you’re a young actor you don’t even put your eyes on those things. Just getting any part in a film is a miracle. Opportunities like those don’t exist for you. It just seemed so outrageous. And then I thought: Hey, maybe this is possible. I had spent time with Francis in San Francisco. He was a leader, a doer and a risk taker. I saw that he carried himself with confidence, and that gave me faith in him. But this wasn’t a thing that was done at the time. Wouldn’t the studio, Paramount, go to older directors who had reputations, not this talented, young avant-garde intellectual? It didn’t fit with my perception of Hollywood.

Then Francis said he wanted me to play Michael Corleone. I thought, Now he’s gone too far. I started doubting whether he was on the phone at all. Maybe I was the one going through a nervous breakdown. For a director to offer you a role, over the phone, not through an agent or anything, and this role of all roles – that was a hundred-million-to-one shot. Who was I, to have this fall into my lap? When I finally hung up the phone with Francis, I was kind of in a daze.

Paramount didn’t want me to play Michael Corleone. They wanted Jack Nicholson. They wanted Robert Redford. They wanted Warren Beatty or Ryan O’Neal. In the book, Puzo had Michael calling himself “the sissy of the Corleone family”. He was supposed to be small, dark-haired, handsome in a delicate way, no visible threat to anybody. That didn’t sound like the guys that the studio wanted. But that didn’t mean it had to be me.

It did mean, however, that I would have to screen-test for the role, which I had never done before, and that I would have to fly out to the west coast to do it, which I just didn’t want to do. I did not care that it was The Godfather. I was a bit afraid of flying and I didn’t want to go to California. But my manager, Marty Bregman, said to me, “You’re getting on that fucking plane.” He brought me a pint of whiskey so I could drink it on the flight, and I got there.

Paramount had already rejected Francis’s entire cast. They rejected Jimmy Caan and Bob Duvall, who were great established actors, well on their way to what they would become. They rejected Brando, for Christ’s sake. It was quite clear walking into the studio that they didn’t want me either. And I knew I wasn’t the only one being considered. Many of the young actors of the day were reading for Michael. That was an unpleasant feeling.

Before I even did my screen test, Francis took me to a barber in San Francisco, because he wanted Michael to have an authentic 1940s haircut. The barber heard that we were making the film and actually stepped back, took it in, and started shaking. We found out later that he had a heart attack. Word was out that there was a lot riding on this film behind the scenes. Paramount executives were irate with one another and having shouting matches. You could feel the tension everywhere. So I did my Zen “this too shall pass” thing. I said to myself, Go to the character. What is going on in the scene? Where are you going? Where did you come from? Why are you here?

I sat through a few days’ worth of screen tests wearing an early version of Michael’s army uniform and a hangdog expression on my face. I always had that look. I guess it was a facade that I carried with me, because it got me through everything. But I must say the scene I was asked to do was not the best one they could have picked. It was Michael, in the opening wedding scene, explaining to his girlfriend, Kay, what his family really did and who all the players were in his father’s operation. It was a mundane scene of exposition, just me and Diane Keaton sitting at a drab little table, drinking glasses of water we pretended were wine, while I talked about Sicilian wedding customs. My interpretation of Michael was like planting a garden; it would take a certain amount of time in the story for the flowers to grow. How am I supposed to bring across my ideas about him in this scene? I couldn’t bring him to life in this scene because nobody could.

But here’s the secret: Francis wanted me. He wanted me and I knew that. And there’s nothing like when a director wants you. He also gave me a gift in the form of Diane Keaton. He had a few actors he was auditioning for the role of Kay, but the fact that he wanted to pair me up with Diane suggested she had an edge in the process. I knew she was doing well in her career and had been appearing on Broadway in shows like Hair and Play It Again, Sam with Woody Allen. A few days before the screen test, I met Diane in Lincoln Center in New York City at a bar, and we just hit it off. She was easy to talk to and funny, and she thought I was funny too. I felt like I had a friend and an ally right away.

When I knew I had the role for sure, I called my grandmother to tell her. “You know I’m going to be in The Godfather? I’m going to play the part of Michael Corleone.” She said, “Oh, Sonny, listen! Grandad was born in Corleone, that’s where he was from.” I didn’t know where my grandfather was born, only that he came from Sicily – once my grandfather got to America and no one was chasing after him, he left it at that. Now to learn he came from Corleone, the very town that gave my character and his family their name? I thought, I must be getting help from somewhere, because how else could such an impossible thing – me getting the role – happen in the first place?

I still had to figure out who Michael was to me. Before filming started, I would take long walks up and down Manhattan, from 91st Street to the Village and back, just thinking about how I was going to play him. Mostly I’d go alone, other times I’d meet my friend Charlie Laughton downtown and we’d walk back uptown together. Michael starts out from a young man we’ve seen before, getting by, a little loopy, a little lumpy. He’s there and not there at the same time. It’s all building up to when he volunteers to take out Virgil Sollozzo and Capt McCluskey, the drug dealer and the crooked cop who conspired to kill Vito Corleone, Michael’s father. All of a sudden, there’s a big explosion in him.

This is mapped out in the novel, because a book can give the narrative as much time as it needs. You wait and see how it unfolds. But what was I going to do in the film?

Before we started shooting, I got together with Little Al Lettieri, who was going to play Sollozzo. He just said to me, “You should meet this guy. It’s good for what you’re doing.” I sort of knew what he meant by that, so I went along with him. One day we took a drive to a suburb just outside the city.

Little Al brought me to a traditional, beautiful, well-kept home. He took me inside and introduced me to the head of the household, a guy who looked like a normal businessman. I shook his hand and said hello, and he was very welcoming. He had a loving family. He had a wife who served us drinks and light snacks on fine porcelain. He had two young sons around my age. I was just some crazy actor who had come into his house, trying to absorb as much as I could. Our conversation remained polite and at the surface level. I never asked Little Al why he had brought me here, but I thought about what he had said before we came, how this visit would be helpful for what I was working on. Little Al knew some guys. Some real guys. And now he was introducing me to one of them.

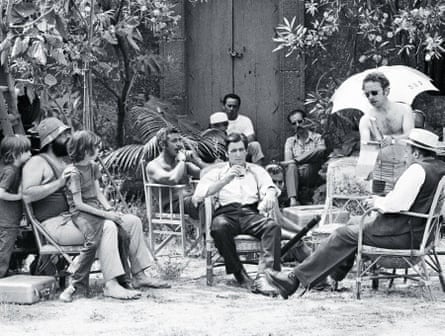

I was being given a taste of how this thing looked and operated in reality, not how it was shown in the movies. Not that our host was going to get into any of those details with us. As a matter of fact, we ended up drinking and playing games. Many moons later, photos from that night surfaced, showing me in a sweatshirt, laughing away with a drink in my hand, while Little Al showed me a gun. A boys’ night out.

I was a kid from the South Bronx. I am an Italian. I am a Sicilian too. I knew what it was to always be assumed that you had at least a connection to organised crime. Any name that ended with a vowel was scrutinised for having possible connections to that world. Instead of being compared to Joe DiMaggio, you were associated with Al Capone.

Most of us will never experience crime, let alone perpetrate it. And yet we’re fascinated with these people who are determined not to live within the rules of society, who are finding another way to go. The outlaw is a particularly American kind of character. We grew up pretending to be Jesse James and Billy the Kid. These were folk heroes. They became part of our lore. The history of the mafia is part of that lore too.

My filming on the Godfather began with its opening wedding sequence, which took about a week out in Staten Island. From my humble day-to-day life, I found myself plunged into the set of a huge Hollywood film, filled with equipment, hot lights and dolly tracks, cranes and booms, microphones hovering overhead, and a company of actors with hundreds of extras, all working under Francis’s direction.

Diane and I spent those first days laughing with each other, having to perform that opening wedding exposition scene from the screen test that we hated so much. On the basis of just that one scene, we were certain we were in the worst picture ever made, and when we’d finish shooting for the day, we would go back to Manhattan and get drunk. Our careers were over, we thought.

Back in Hollywood, Paramount started to look at the film that Francis had shot, and they were once again questioning whether I was the right actor for the part. The rumour had got out around the set that I was going to be let go from the picture. You could feel that loss of momentum when we shot. There was a discomfort among people, even the crew, when I was working. I was very conscious of that. The word was that I was going to be fired, and, likely, so was the director. Not that Francis wasn’t cutting it – I wasn’t. But he was the one responsible for me being in the film.

Finally, Francis determined that something had to be done. One night he called me to meet him at the Ginger Man, a restaurant and watering hole for thirsty Lincoln Center types, where actors, dancers, maestros, and stagehands all lined up at the bar. He was having dinner there with his wife, his kids and a small group, and when I went in and found him at his table, he said, “Listen, I want to talk to you a minute.” He didn’t invite me to sit down with them. I stood there wondering, What’s he doing? He’s cutting his steak and looking at me like I’m not part of anything – like I’m just some isolated actor who had come looking for a handout. Finally, Francis said, “You know how much you mean to me, how much faith I had in you.” At this point we had been shooting The Godfather for about a week and a half. And Francis said, “Well, you’re not cutting it.”

I felt that one in the pit of my stomach. It’s when it finally hit me that my job was on the line. I said to Francis, “What do we do here?” He said, “I put together rushes of what we’ve shot already. Why don’t you take a look at it yourself? Because I don’t think it’s working. You’re not working.”

I went into a screening room the next day. And when I looked at the footage, all scenes from very early in the film, I thought to myself, I don’t think there’s anything spectacular here. I didn’t know what to make of it. But the effect was certainly what I wanted. I didn’t want to be seen. My whole plan for Michael was to show that this kid was unaware of things and wasn’t coming on with a personality that was particularly full of charisma. My idea was that this guy comes out of nowhere. That was the power of this characterization. That was the only way this could work: the emergence of this person, the discovery of his capacity and his potential. By the end of the film, I hoped that I would have created an enigma. And I think that’s what Francis was hoping for also. But neither one of us knew how to explain it to the other.

after newsletter promotion

It was always thought that Francis reorganised the shooting schedule to give the doubters back in Hollywood some incentive to believe in me and keep me in the picture. The jury’s out on whether he did that deliberately, and Francis himself has denied that he orchestrated it for my benefit, but he did move up the filming of the Italian restaurant scene, where the untested Michael comes to take his revenge on Sollozzo and McCluskey. That scene was not meant to be filmed until a few days later, but if something hadn’t happened to let me show what I was capable of, there might not have been a later for me.

So over the course of an April night I shot that scene. I spent 15 hours that day in a tiny restaurant, with Little Al Lettieri and the magnificent Sterling Hayden, who played McCluskey. The two of them truly were precious to me. They knew I was going through a difficult time, feeling like I had the world on my shoulders, knowing that any day the axe could fall on me. Here we were in a dead, fetid room that was being filled with smoke and hellish heat – we had no trailers to escape to, no production assistants coming up and asking, “Can we get you some water?” None of that. I was just sitting there, thinking, How do you stand this stuff? The absolute ennui of it could actually kill you.

Sterling and Al Lettieri helped keep up my morale; they set a tone and were role models for me. But eventually the script called for me to excuse myself to use the bathroom, find a hidden gun, and blow their brains out. Then I had to run out of the restaurant and make my escape by jumping on to a moving car. I had no stand-in. I had no stuntman. I had to do it myself. I jumped, and I missed the car. Now I was lying in a gutter on White Plains Road in the Bronx, flat on my back and looking up at the sky. I had twisted my ankle so badly that I couldn’t move.

Everyone on the crew had crowded around me. They were trying to lift me up, asking me: Was my ankle broken? Could I walk? I didn’t know. I lay there thinking, This is a miracle. Oh God, you’re saving me. I don’t have to do this picture any more. I was shocked by the feeling of relief that passed over me. Showing up for work every day, feeling unwanted, feeling like an underling, was an oppressive experience, and this injury could be my release from that prison. At least now they could fire me, recast another actor as Michael, and not lose every dime they’d already put into the picture. But that’s not what happened.

They filmed the rest of the car-jumping scene with a stunt guy who appeared out of nowhere, and they shot my ankle up with cortisone until I could stand on my feet again. Then Francis showed the restaurant scene to the studio, and when they looked at it, something was there. Because of that scene I just performed, they kept me in the film. So I didn’t get fired from The Godfather. I just kept doing what I did, what I had thought about on those lonely walks up and down the length of Manhattan. I did have a plan, a direction that I really believed was the way to go with this character. And I was certain that Francis felt the same way.

I had been introduced to Marlon Brando briefly at a dinner with all the cast members before we started filming. Now, as we were getting ready to do the scene where Michael finds Vito in the hospital, Francis said, “Why don’t you and Brando have lunch together?” This was going to be the big talk. I actually didn’t want to talk to him. I thought it was not necessary. The discomfort I felt at just the thought of it – You mean I have to have lunch with him? Seriously, it fucking scared me. He was the greatest living actor of our time. I grew up on actors like him – larger than life people like Clark Gable and Cary Grant. They were famous when fame meant something, before the bloom went off the rose. But Francis said you have to and so I did.

I had my lunch with Marlon in a modest room in the hospital where we were filming on 14th Street. He was sitting on one hospital bed, I was sitting on the other. He was asking me questions: Where am I from? How long have I been an actor? And he was eating chicken cacciatore with his hands. His hands were full of red sauce. So was his face. And that’s all I could think about the whole time. Whatever his words were, my conscious mind was fixated by the stain-covered sight in front of me. He was talking – gobble, gobble, gobble, gobble – and I was just mesmerised. What was he going to do with the chicken? I hoped he wasn’t going to tell me to throw it in the garbage for him. He disposed of it somehow without getting up. He looked at me in a quizzical way, as if to ask, What are you thinking about? I was wondering, What is he going to do with his hands? Should I get him a napkin? Before I could, he spread both his hands across the white hospital bed and smeared the sheets with red sauce, without even thinking about it, and he kept on talking. And I thought, Is that how movie stars act? You can do anything.

When our lunch was over, Marlon looked at me with those gentle eyes of his and said, “Yeah, kid, you’re gonna be all right.” I was taught to be polite and grateful, so I probably just said thank you to him. I was too scared to say anything at all. What I should have said was “Can you define ‘all right’?”

What I think audiences received from The Godfather, what brought it across and really gave it its impact, was this idea of family. People identified with the Corleones, saw themselves somehow in them, and found themselves connecting to the characters and their dynamics as brothers and sisters, parents and children. The film had Mario Puzo’s exciting drama and storytelling, the magic of Coppola’s interpretation, and real violence. But in the context of that family, it all became something else. It wasn’t just people from the city who related to the Corleones – that sense of familiarity carried the film to every part of the world.

Marlon showed me generosity, too, but I don’t think he saved it all for me, because he shared it with the audience. It’s what made his performance so memorable and so endearing. We all fantasise about having someone like Don Vito we can turn to. So many people are abused in this life, but if you’ve got a Godfather, you’ve got someone you can go to, and they will take care of it. That’s why people responded to him in the film. It was more than just the bravado and the boldness; it was the humanity underneath it. That’s why he had to play Vito larger than life – his physical size, the shoe polish in his hair, the cotton in his cheeks. His Godfather had to be an icon, and Brando made him as iconic as Citizen Kane or Superman, Julius Caesar or George Washington.

But Francis had a lot on his shoulders, as I would learn when we were working on the funeral sequence for Vito. It was a big scene we shot out on Long Island that involved a large amount of the cast and took a couple of days. The sun was going down and I heard “Wrap! Wrap!” They told me I was done for the day. So naturally I’m happy because I get to go home and have some fun, whatever that means. I was on the way to my trailer saying to myself, Well, I didn’t fuck up too much. I had no lines, no obligations, and that was fine.

As I was heading back, I began to hear the sound of someone crying, which you sort of expect in a graveyard. I looked around to see where it was coming from. And there, sitting on a tombstone, was Francis Ford Coppola bawling like a baby. Profusely crying. Nobody was going near him, so I went up to him, and I said, “Francis, what’s wrong? What happened?” He wiped his eyes with his sleeve, paused, looked up at me, and said, “They won’t give me another shot.” He had wanted to film another setup that day, and he had not been allowed it. Even he had to answer to someone else. And he wanted this so badly that to have it denied had actually wounded him.

One never knows if a film is going to be great. But there in that graveyard I thought, If this is the kind of passion that Francis has for it, then something here is working. I knew I was in good hands.

Before the Godfather had its premiere in New York, I had seen it only once, a few months earlier, when Francis had shown me an unfinished cut. At the end of that screening, I gave Francis notes on my performance, and he looked at me with an expression of quasi-disgust. Of course when I’m looking at an unfinished film, I can’t help seeing things that I might do differently. But you’d think I would understand that it was not my place to say this to the director of the film, who had just spent the last year of his life dangling from the edge of a cliff by his fingernails to get it made. I was insensitive: he had the grace to show it to me and I came in worried about my performance and not the great film he had made. Sometimes you’re a little unconscious as a young actor. You have other things on your mind, and all forms of grace and etiquette go out the window due to your vain impulses and stupid ego. I’ve seen it in others, I must say. I hope I’m not still that way, but the jury’s out on that one.

Back in 1972, the effect that the film’s release had on me was immediate. It happened at light speed. Everything changed. A few weeks after it came out, I was walking on the street and a middle-aged woman came up to me and kissed my hand and called me “Godfather”. Another time, I went into a grocery store to get a container of coffee to go while Charlie waited for me outside on the sidewalk. And a woman approached him and asked, “Is that Al Pacino?” He said to her, “Yeah.” She said, “Oh, really? He’s Al Pacino?” He said to her, “Well, somebody’s gotta be.”

The film had not been out that long, so I continued to go about my normal daily life as if nothing had changed. One day I was standing at a kerb, waiting for the light to change, and this pretty redhead was standing there with me. I looked at her. She looked at me. I said, “Hi.” She said, “Hi, Michael.” And I just went, Whoa. Oh my God. I am not safe. Anonymity, sweet pea, the light of my life, my survival tool – that’s gone now. You don’t appreciate it till you lose it.

Source: theguardian.com