Jeff Most remembers the last time he saw Brandon Lee alive. “I was in my office on Carolco lot in Wilmington and I was on the phone,” he says. “Brandon was in this white shirt and he walked by and he was waving to me through the window.

“I held the phone down for a second and waved back and it was like, ‘Yeah, we’re not waving goodbye!’ I literally said to the person on the phone it’s so bizarre, Brandon is waving to me like he’s waving goodbye but he knows he’s got another two weeks of shooting to go.”

Less than an hour later Lee, a 28-year-old actor, was accidentally shot in the abdomen while filming a scene for The Crow, a movie developed and produced by Most, directed by Alex Proyas and released 30 years ago this week. He died in hospital.

Hopes that on-set health and safety have so improved that such a tragedy could never happen again were dashed in 2021 when, during production of the western film Rust in New Mexico, the actor Alec Baldwin was rehearsing with a revolver when it fired a live round, killing the cinematographer Halyna Hutchins.

Soon after, a social media account run by Lee’s sister Shannon tweeted: “No one should ever be killed by a gun on a film set. Period.” The accident was like the resurfacing of an old nightmare for Most, who knew Hutchins personally and felt his heart break all over again.

In an interview with the Guardian he discusses these uncomfortable parallels, his memories of Lee – the son of martial arts star Bruce Lee – and the genesis of The Crow, a haunting film about death and an avenging angel that spawned sequels and, later this year, a remake starring Bill Skarsgård, Danny Huston and FKA Twigs.

Based on an adult comic book of the same name, The Crow follows Eric Draven, a rock guitarist murdered by a gang along with his fiancee Shelly (Sofia Shinas) on the eve of their Halloween wedding. He is summoned by a mysterious crow to come back from the dead with supernatural powers to exact justice.

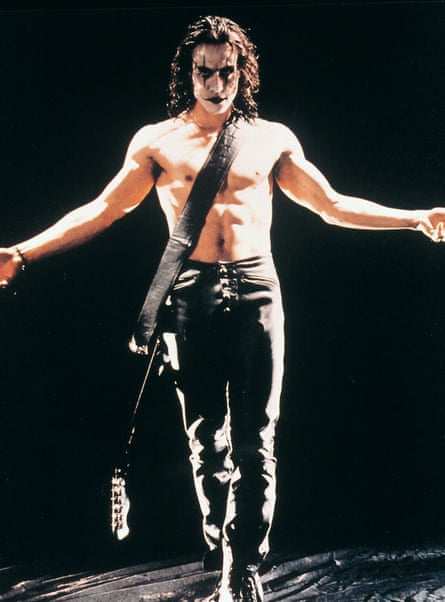

A generation later, Lee’s screen charisma remains incandescent. His gothic features and white-painted face foreshadow the revenge-seeking Johnny Depp in Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd. The Crow’s bleak cityscape – it’s mostly night, mostly raining – is of a piece with various incarnations of Batman’s Gotham, while its revelling in violence as an answer to lawlessness recalls RoboCop.

The film is now seen as a cult classic but almost never got made. Speaking from Riga, Latvia, one of his bases, Most recalls finding The Crow in a comic book store in Los Angeles. “I said, I want to make this movie. I was just blown away by everything I read in the pages.”

He made contact with its author, James O’Barr, who had created The Crow to deal with his grief after losing, at the age of 18, his fiancee when she was killed by a drunk driver. He was already considering an offer from a rival producer.

“I just jumped in. I said look, I love this comic. I will make the first R-rated live-action comic book adaptation ever made. We will make this as dark a movie as you’ve draw in this comic.” O’Barr agreed to the offer and so Most and collaborator John Shirley set about writing treatments while also searching for studio backing.

But Most says: “I knocked on every door I could. I think I ended up at one point I had 51 passes. Everyone in Hollywood just said this is way too dark, you can’t make this, no one will ever make this.”

But his fortunes changed thanks to his previous work in New York as an assistant to Barbara Lieberman, a producer of the variety show Saturday Night Live who had recently moved to Los Angeles. When he told Lieberman about his plight over lunch, she put him in touch with producer Ed Pressman, who came in as co-producer but was content to let Most take the lead.

With an estimated $23m budget, Most recruited the Australian-based Proyas as director and, with Shirley, rewrote the screenplay, setting the start of the film on “Devil’s Night”, referring to the night before Halloween, which had become notorious in Detroit for arson and vandalism.

“I felt it was very important to concretise the rules of this world, to have a bigger plot device behind it as the machinations of evil that went on. When the film was released as of that year, in 94, from what I understood that was the end of Devil’s Night. We put such attention on it in the movie I suppose it aided in raising consciousness about it in Detroit and maybe it stopped people from doing it.”

Lee, who was only eight when his famous father died from cerebral edema in 1973, spent most of his childhood in Hong Kong and always wanted to be an actor. He appeared in action films such as Showdown in Little Tokyo and Rapid Fire in the early 90s and seemed poised for a major career breakthrough. He was also a dedicated craftsman and a winning personality who was engaged to be married.

Most developed a friendship with him before filming began in Wilmington, North Carolina. They would watch laser discs with Proyas and screenwriter David Schow. “David would go to Little Tokyo and Chinatown in LA to find movies that we could use as references for fight scenes and we’d watch the movies and talk about the script.

“Brandon would ultimately do some kind of crazy thing or practical joke because he was full of life; he would do some insane things to get laughs out of us. He’d become a real friend. He was such a beacon of light and uplifting, generous and caring – the kind of person everybody in the world would want as a best friend.”

Most continues: “He exemplified all those beautiful qualities in an individual. He was smart. He was intuitive. He was so masterful about understanding himself in relation to this role and what he wanted to bring to it and literally throwing out all of his training in martial arts, which was significant and tremendous. He wanted to create his own language of movement because he understood this character.

“This was not a martial artist; he’s a musician; he’s a guy who has never probably gotten in a fight in his life and yet he comes back with this tremendous power and a mission. Brandon tried to envision a mental approach to how he could create this individual who at once has to do these horrible things and yet it’s the farthest thing from anything that would have been in the persona of the character while they were alive. It was an incredible, artful and intently thought out performance. That’s what is so resonant with people today.”

Most remembers how each day Lee would wake up at 5.30am, starve himself and work out. Given the character, Lee insisted on learning how to play the guitar, so Most found a teacher for him in Wilmington. “You couldn’t throw more things at the man and he took it all in like a sponge.”

Then came catastrophe. Late at night, filming one of the final scenes, actor Michael Massee, who played drug dealer Funboy, pulled the trigger on a prop gun aimed at Lee, who was 15-20 feet away. It was supposed to fire a blank cartridge but a portion of a dummy bullet had inadvertently been left in the barrel of the gun from a previous scene. It entered Lee’s abdomen and lodged in his spine. He died in hospital hours later of internal injuries, blood loss and heart failure on 31 March 1993.

Most audibly draws breath as he thinks back to that night. “It’s all very hard to to talk about,” he says. “It’s a big jumble in certain respects but it’s also as clear as yesterday in others.

“I left the studio at midnight and the phone was ringing literally in the house that I was staying at as I walked through the door. I was originally assured that it was nothing – a dummy wad hit his vest, he had the wind knocked out of him, do not worry, Brandon’s fine. At that point that’s what everyone on the crew thought.

“There was no blood when the bullet went in. It just cut into him, unlike a bullet wound, and spun around inside we learned later. It was a horrific night. It was beyond belief that the accident occurred in the first place. We were all unbelievably devastated.”

The following morning, Lee’s co-star Sofia Shinas told Most that Lee had rejected advice to wear a flak jacket because he thought it would be visible on camera. “She turned to him and said, you’ve got to wear the flak jacket and he said, no, look, I’m not worried, if it’s my time to go, it’s my time to go home. Of course, had he worn the jacket, it probably would have prevented the fatal wound.”

Most adds: “He so touched everyone on the crew. We were all beyond broken. This was a man who was a friend to all of us, who was an incredible artist, incredible actor, incredible human being. It was truly for me one of the most tragic things I had experienced in my life at that point and and still to this day, just something that was very difficult to get over and to understand how it could have happened in any way, shape or form.”

The death was ruled an accident and no criminal charges were brought against Massee, but he told the Telegraph in 2005: “I don’t think you ever get over something like that.” The Occupational Safety and Health Administration fined the production $84,000 for violations found after Lee’s death, but the fine was later reduced to $55,000.

Lee was buried next to his father in Seattle. His remaining scenes were filmed using his stunt double, Chad Stahelski, who went on to direct the John Wick films. The Crow was finally released on 13 May 1994, dedicated to Lee and his fiancee, and went on to gross more than $50m worldwide at the box office.

Lee’s death led to changes in how firearms are treated on sets. But nearly three decades on, history rhymed in terrible fashion.

Baldwin, the lead actor and co-producer for Rust, was pointing a revolver at Hutchins during rehearsal whenit went off, killing the cinematographer and wounding director Joel Souza. A jury in New Mexico found the armourer Hannah Gutierrez-Reed, who put a live round into the gun, guilty of involuntary manslaughter. Prosecutors in New Mexico are pursuing an involuntary manslaughter charge against Baldwin in a case scheduled for trial in July.

Most reflects: “I’m brokenhearted at the loss of Halyna. She was a friend to me as well as my wife, who is a cinematographer. We met Halyna shortly after she was out of AFI [American Film Institute]. She was a dear, wonderful woman, somebody we very much had designs on working with.

“You want to look at the silver linings of what can be learned in situations and certainly what was learned in the loss of Brandon was a routine formula of checking the barrel of a gun to make sure that there is no bullet, no protrusion of any sort, that the barrel is clean and clear and is held to the light.

“And a practice in which the first assistant director, oftentimes the key grip, the prop master are all involved with the actor, making certain a weapon is cold when it’s cold, is hot when it’s hot, and there is nothing in the barrel or chamber that could be ejected.

“To see that in the almost 30 years between the movies we hadn’t improved upon that was certainly devastating. I will say that I find it tragic and beyond belief that Alec Baldwin has been held any bit responsible for this. As a producer with more than 30 years’ experience and numerous action films under his belt, I can assure you that there is no place in the world in which an actor is responsible for the weapon they’re handling.”

Most concludes: “There’s no place for anything but absolute safety on a set and it all brought back memories of the terrible tragedy with the loss of Brandon. It should not have been repeated and I hope it won’t ever be again.”

After the Rust tragedy, a petition to ban the use of real firearms on film sets was circulated, and last year the Los Angeles Times newspaper argued in an editorial that the time for such a measure had come. Director Guy Ritchie announced that he was no longer using real guns in his productions.

Bridget Baiss, author of The Crow: The Life, Death, and Rebirth of a Classic Film, a revised and updated edition of which will be published in June, says: “Between The Crow and Rust nothing really changed except people got more aware and more minded about it. Then that generation retired and things got left behind.

“But now people are focused on it and it has changed. More film-makers and television productions are making the choice to use special effects for bullets; they don’t look 100% real to people who are gamers but they look pretty real to the average person. There are other methods you can use that are not dangerous.”

Speaking from McLean, Virginia, Baiss adds: “The thing on Rust was actually even more egregious in way than The Crow – even more careless. But I think things are changing. I hope so.”

Source: theguardian.com