I

In early 2022, Wim Wenders was unexpectedly invited to Tokyo to view some public toilets. The invitation came from the Tokyo Toilet art project, which had hired notable architects and designers to construct 17 visually appealing public toilets in different areas of the Shibuya district. Wenders shares, “They reached out to me and said, ‘We’re aware of your interest in Japan and architecture.’ They then asked me to visit and see the stunning toilets, and potentially create a series of short documentary films about them.”

The timing of the invitation was perfect for Wenders, as he was longing for Tokyo, a city he had frequently visited after filming a documentary about fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto in 1989. He describes it as a dream come true.

Soon after, he visited the city while taking a break from filming the final scenes of his documentary Anselm, which focused on the German artist Anselm Kiefer. The city left a strong impression on him, leading him to believe that the tranquil and picturesque nature of the area would be better captured in a fictional movie. He assured his hosts that he could create this film with a small budget and within the same 16-day shoot schedule. To his surprise, they agreed almost instantly. Reflecting on the experience, he says, “It all happened so quickly, but fast can be beautiful. Fast can be a blessing. Fast can unleash creativity.”

The final outcome, however, is a remarkable example of slow-paced cinema. Perfect Days is a movie where not much occurs, but the few events are strangely captivating. Co-written with Japanese author Takuma Takasaki, it consists of multiple small variations on one main theme: the daily work routine of Hirayama, a solitary yet satisfied person whose occupation is to clean and upkeep the Shibuya restrooms. “It is a modest film, indeed,” Wenders acknowledges. “But it was also my first film post-pandemic. I saw it as a fresh start for me, so I wanted it to hold significance.”

During a time when there are many ambitious and lengthy films like Oppenheimer and Killers of the Flower Moon, Wenders’s contemplative portrayal of simple life has resonated with both critics and audiences. In May, Kōji Yakusho, who portrays Hirayama, received the Best Actor award at Cannes. “His character is the heart of the film,” Wenders commented.

Where did the inspiration for the stoic protagonist originate from? “I created him in my mind and we chose him within two weeks. We understood from the beginning that we required someone who was observant of their surroundings, able to convey their life through their eyes. It takes a skilled actor to convey subtle movements, such as opening a door or looking up at the sky, and make them significant. I only knew one actor who could fulfill this role, and that was Kōji.”

Display the image in full screen mode.

The movie is being considered for the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film, marking the first time that Japan has chosen a non-Japanese director. Takasaki praises Wim’s impressive understanding of Japanese culture and describes their collaboration as a wonderful experience. Through Wim’s perspective, Takasaki was able to reconnect with his country, culture, and beliefs.

I meet Wenders in the expansive headquarters of his production company, Road Movies, in the Mitte district of Berlin. We chat across a long table in a back room in which a tall, elaborate African carving stands sentinel by the door. One of Wenders’s large-format landscape photographs of the American west stretches across the back wall. At 78, the director exudes a relaxed calmness, his answers considered and often very detailed. “Films are a product these days,” he says ruefully at one point. “The beauty of Perfect Days is that I had nobody looking over my shoulder. I could do what I wanted. Takuma was a great help, but there was no control. They let the two of us just run free. There was only a little money but complete freedom.”

His 23rd film, Perfect Days, has been praised by reviewers for being a comeback for the director, who has recently received more recognition for his documentaries. These include Pina from 2011, a portrayal of the austere and influential dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch, and Pope Francis: A Man of His Word from 2018, in which he was able to gain unprecedented access to the current pope. However, none of these films fully prepared me for his latest work, Anselm, which I tell him is the most ambitious and enlightening exploration of compulsive artistic genius I have ever encountered.

Display the image in full screen mode.

“I am pleased that we were able to successfully complete this film, despite the challenges we faced during the pandemic,” he explains. “We diligently followed all safety protocols and it took a total of three years to make, including seven shoots in various locations and several months of editing in between. While it may have been a longer process, I believe it was necessary in order to properly capture the magnitude of this man’s work.”

I viewed Anselm and Perfect Days back to back and was impressed by their stark contrast in content and goals. “Absolutely,” he chuckles. “They are practically polar opposites. Anselm Kiefer is by far the hardest worker I’ve ever encountered. He is unrelenting. In contrast, Perfect Days follows a man who lives a modest, minimalist lifestyle. So, one focuses on abundance while the other centers on minimalism.”

Yakusho’s portrayal of Hirayama, the janitor, is flawless. He appears as a man who is displaced in time, having abandoned a more privileged life for reasons that remain unclear. Hirayama resides in a modest, spartan apartment in a working-class neighborhood. He indulges in reading literary novels he finds in secondhand bookstores and listens to a limited selection of cassettes – The Kinks, Nina Simone, and The Velvet Underground – while commuting to and from work in his van. During his lunch break, he quietly observes the ordinary world around him and occasionally takes photographs of the trees nearby. In the evenings, he frequents the same cafe and bar.

He has brief but meaningful encounters with various characters as they pass by, such as his unreliable coworker, his loving niece, and a stranger who is terminally ill. When his wealthy, estranged sister arrives in a fancy car, it briefly disrupts his peaceful routine and reminds him of his past life. However, he remains distant and content, finding inner peace through the simplicity of his daily life. Wenders describes him as a secular monk.

Display the image in full screen.

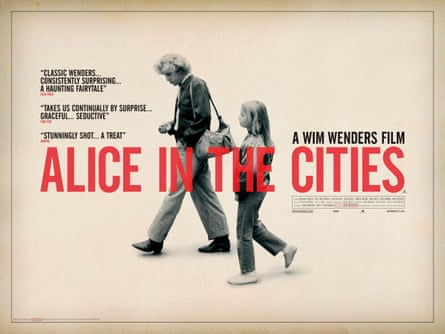

Hirayama stands out among the restless protagonists of the director’s earlier works, such as Philip Winter, the mysterious German writer adrift in the vastness of America in 1974’s “Alice in the Cities,” or Travis Henderson, haunted by his past as he wanders through the endless desert in 1984’s “Paris, Texas.” He nods in agreement, stating that these films revolve around characters searching for something that they ultimately do not find. In contrast, Hirayama is content and not in search of anything. He takes a moment to reflect before sharing that all of his films explore the question of how to live, although it took him some time to realize this as he was also searching for answers. “Perfect Days” provides a precise answer and may evoke a longing for a simpler lifestyle and less consumption in viewers. In many ways, Hirayama exemplifies a perfect way of living.

W

Wim Wenders grew up during the 1970s and emerged as a filmmaker alongside other influential German directors like Werner Herzog and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who were part of a movement called New German Cinema. Born in 1945 in Düsseldorf, Wenders took a roundabout path to filmmaking. He was raised Catholic and briefly considered becoming a priest before studying medicine and philosophy. However, after dropping out of university to pursue painting in Paris, he became captivated by cinema and would often watch multiple films in a single day at his local Montparnasse theater. He eventually returned to Germany in 1967 and worked as a film critic for various publications, including Der Spiegel, while also attending film school in Munich. According to Wenders, the same film school had rejected Fassbinder and lacked even basic equipment like cameras.

Wim Wenders recalls receiving a powerful and harsh message from visiting lecturer Werner Herzog, who he describes as slightly older. According to Wenders, Herzog’s approach to teaching cinema was unlike any other, and he remembers the blunt directive to drop out of school and start making films immediately. Herzog’s words were clear and forceful, urging the students to leave the school and begin pursuing their passion without delay. Wenders reflects on this experience with a laugh, acknowledging the intensity of Herzog’s unconventional teaching style.

I inquired if you followed his suggestion. “No, but it did prompt me to change my perspective on film-making. I had a 16mm camera and began making films outside of school. I also became the designated cameraman for all the students due to my possession of a small Bolex camera. From that point on, we produced a movie every week. Our learning was primarily through hands-on experience, as Werner’s insults had pushed us to do so.”

Wenders completed his early trilogy of “road movies” – Alice in the Cities, The Wrong Move, and Kings of the Road. He gained more recognition with his stylish and noirish adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s novel Ripley’s Game, titled The American Friend, released in 1977. From 1974 to 1982, Wenders was married and divorced three times, all to actors. One of his former wives, Ronee Blakley, starred in his 1985 docu-drama I Played It for You. He has been married to his current wife, Donata, a photographer and occasional collaborator, since 1993. Despite his high level of creative output, Wenders describes the 1970s as a challenging time personally. He sought help from Freudian analysis and attended sessions five times a week. He considers it a worthwhile detour from his work.

In the 1980s, Wim Wenders had a difficult experience while making the movie “Hammett,” which was a noir thriller commissioned by Francis Ford Coppola. Coppola then demanded a complete re-edit of the film. However, Wenders regained his creative inspiration with his 1984 film “Paris, Texas.” This movie also featured a solitary traveler, played by Harry Dean Stanton, and was known for its stunning landscapes captured by Wenders’s longtime collaborator, Robby Müller. The haunting music and evocative imagery of billboards, train tracks, and desert highways further solidified Wenders’s reputation as a European filmmaker with a romantic American sensibility.

Display the image in full screen mode.

A few years later, there was a sudden change when another movie, Wings of Desire, was released and became known as the film that put the director on the map. This European film was set in Berlin, the director’s hometown, and featured angels who roamed the city unseen. It remains one of the most captivating depictions of the city’s unique atmosphere in the years leading up to reunification. One of the film’s cameo appearances was made by Nick Cave, who performed with his band, the Bad Seeds, at a local club. At the time, he was living in Berlin and upon rewatching the film, he was struck by its accurate portrayal of the city during that era: the locations the angels traversed, the unconventional bars they frequented, and the overall post-punk vibe. The looming presence of the Berlin Wall added a political dimension to the city, which also had a thriving artistic movement that attracted many creative individuals.

According to Wenders, it was difficult for him to come to terms with being a German artist, which he eventually recognized while making Wings of Desire. He explains that this film was his way of embracing his identity as a German. Prior to this, he had been avoiding his homeland and instead exploring other nations and cultures, feeling that he was better off outside of Germany.

W

Enders and Anselm Kiefer were both born in the same year that Germany surrendered in World War II. It took Enders three years to create his work on Anselm, leading some to wonder if he felt a connection with his subject due to their similar backgrounds. After some thought, Enders responds, “Yes and no. We shared many experiences in our youth. I grew up on the Rhine and spent my childhood near the river, just like Anselm who lived a few hundred miles north. We were both taught by Nazi teachers and lived in a country that had to rebuild itself and look towards the future. However, for a long time, this future was built on the condition of forgetting the past.”

Wenders’s intricate and multi-faceted documentary reveals the underlying theme of Kiefer’s art, which serves as a long investigation into the Germany of their shared birth. This includes the ruins and silences, as well as the dark shadow of the Nazi era and the subsequent amnesia. Wenders reflects, “As a young person, you can sense that something is not right, but you can’t quite grasp it. As you grow older, you begin to see it more clearly and it becomes unsettling. Personally, it made me so uncomfortable that as a teenager, all I wanted was to escape. Anselm, on the other hand, had the opposite instinct: he wanted to confront it head-on, to expose it and remind people to remember. He chose to stay and face the monster, while I wanted to avoid it.”

He states that it took him a while to fully accept his German identity and embrace his inner romanticism. This realization primarily occurred during his time in America, where he attempted to conform and create an American-style film, but ultimately realized that his German nature prevented him from doing so.

Wenders has embarked on a lengthy journey as a filmmaker that largely reflects his personal interests, particularly his strong spirituality. The angels depicted in Wings of Desire and its highly-regarded sequel Faraway, So Close! are drawn from Christian imagery, representing benevolent beings who oversee goodness and grace. In Perfect Days, Hirayama leads a virtuous life, though his beliefs align more with Zen Buddhism than Christianity. The director has stated that his documentary on Pope Francis is the culmination of all his previous works. Interestingly, despite being raised Catholic, Wenders converted to Protestantism in the 1970s after a profound experience at a lively Presbyterian church in Los Angeles. When asked about his current religious beliefs, he confirms that his later films suggest a continued connection to spirituality.

“I consider myself to be a highly spiritual individual,” he responds. “This means that I am deeply religious, but not a supporter of organized religion. Upon my return to Berlin, I was unable to find a church that had the same vibrant atmosphere as some American churches, with a strong sense of community. The type of religion I strive for is similar to the early churches, almost like a communist society. The limited information we have about them has greatly influenced my life, with their communal living and shared resources, leading simple lives. Unfortunately, this way of life has been lost.”

Wenders has brilliantly portrayed Hirayama in Perfect Days as a modern-day saint, living a solitary but fulfilled life without the constraints of organized religion. The film subtly celebrates the idea that a simple yet mindful existence can attain a spiritual essence. This sentiment resonates with Wenders’ admiration for Yasujirō Ozu, whose films have the power to alter one’s perspective on the world with their depiction of ordinary family stories infused with humanity and spirituality.

Although he is disappointed by the dominance of franchise movies in today’s film industry, he maintains a hopeful outlook. However, his optimism has been challenged recently. He has been working on a science-fiction utopian film, titled “Peace By Peace”, for the past five years. A significant aspect of the film revolves around Palestine, but he laments that he can no longer continue with his original vision due to the current state of the country. He expresses concern that Palestine may no longer exist and fears that it will become a barren wasteland.

In summary, I inquire if he reflects on his artistic journey as a continuous path driven by similar concerns. He responds, “No, I feel like I am in a different stage now. When I was younger, the characters in my films mirrored my own quest in a peculiar manner. The act of creating a film was a pursuit in itself, a journey to uncover the underlying truth of the narrative. However, there is less space for that now, which is why I focus on making documentaries.”

He stops once more, taking a prolonged pause. “One of the earliest lessons I learned was that creating films can be a transformative experience. It changes you as a person. Sometimes, I wonder what my life would be like if I pursued my childhood dream of becoming a painter. I believe I would have become a solitary, reserved individual. However, film-making has broadened my thinking and my character. I used to be quite isolated, but that is not the case anymore.”

-

The UK and Ireland release date for Perfect Days is February 23rd.

Source: theguardian.com