This statement highlights the lack of understanding during a time when tolerance was less common, and the lasting emotional harm it still causes.

Peter Tatchell

If you’re seeking a heartwarming, optimistic film about the LGBTQ+ community, All of Us Strangers may not be the right choice. This movie delves into a somber, emotionally-charged love tale that blurs the lines between what is real and what is imagined.

Adam is a gay man who is emotionally damaged and feels isolated. He is currently facing difficulties accepting the loss of his parents at the age of 12 and trying to overcome the feeling of being an outsider due to his sexuality.

His internal conflict causes him to close off his willingness to engage in relationships and causes him to reject the advances of Harry, a younger and seemingly more self-assured neighbor. This leads Adam to enter a world of contemplation, questioning the possibilities.

The two men engage in a fervent romance, filled with companionship, love, and acceptance that Adam has desired for a long time – until it abruptly and heartbreakingly ends. However, Adam finds solace in imagining a conversation with his deceased parents and finally understanding that they genuinely loved him. It is not a completely dismal ending after all.

The movie’s honest examination of the frequently strained and problematic connections between numerous middle-aged gay men and their parents is accurate. It showcases the lack of knowledge and bias during a less accepting time period, and the lasting emotional harm it still causes, even years later, in many (though not all) present-day relationships involving older gay men.

These individuals also experienced the distress of the “gay plague” and widespread fatalities from Aids before the advent of effective treatments in the mid-1990s. This is briefly acknowledged in discussions between Adam and his mother, but nothing more is mentioned. There is no acknowledgement of the heightened persecution by police during the 1980s and 90s, which also resulted in many gay men being emotionally shattered.

Of course, no one film can cover all aspects of the gay experience. But as well as this brutally honest portrayal of anguish and pain, I wish there were more films like 120 Beats Per Minute’s equally harrowing but ultimately uplifting portrayal of gay love and loss, set amid the backdrop of the fightback against Aids by Act Up-Paris.

There is a lack of significant films that depict LGBTQ individuals who have not succumbed to homophobia. It would be great to have a portrayal, whether through a drama or documentary, that showcases the personal and political experiences of the courageous activists from the 1970s Gay Liberation Front and OutRage! in the 1990s. This is something that has been needed for a long time.

‘Needed hotter sex, more grit, less sanguine miserablism’

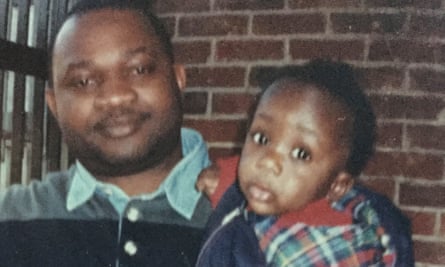

Jason Okundaye

I can empathize with those who shared their experience of finishing All of Us Strangers in tears, but personally, I did not have the same reaction. The film seemed to be pushing for an emotional response from me. I would have been particularly susceptible to its attempts at manipulation, as I am a gay individual who has lost a parent and has many straight friends. I am also aware of the potential loneliness I may face when my friends begin to have families and our lives diverge.

All of Us Strangers is a desperate plea against the loneliness and dysfunction queer men can experience at different stages of their life and for different reasons. I did find aspects relatable – Adam ages and finds himself still in a flat by himself, unsure about what family means, or what the future holds for him – it feels familiar. But plenty of it was too ham-fisted and cliched about the contours of gay men’s lives.

I often envision discussions with my deceased father, who passed away before I fully accepted my sexuality. The film effectively portrays the sorrow experienced by gay men who lost their parents at a young age. While others may long for their parents to witness their marriages and children, our grief is complicated by uncertainty about our relationship with our parents if they knew our true selves. However, when Adam discloses his sexuality to his mother, her struggle to understand same-sex marriage and the “falling tombstone disease” felt unoriginal and lacking in emotion. Perhaps this is intentional – these are ghosts stuck in the mindset of when they died – but it also reveals the film’s reliance on the audience’s personal connection.

The conversation between Adam and Harry highlights their generational gap, as they discuss their varying understandings of terms like “gay” and “queer”. However, their sexual differences and potential for playful conflict are not explored. Despite this, the chemistry between the actors elevates even the most simplistic dialogue, particularly when Adam loses control while kissing.

My understanding of Harry is that he passed away after being rejected by Adam at the door, and Adam was communicating with his ghost throughout. The supernatural occurrences force Adam to confront things he has been avoiding in his life – dealing with grief and being close with others. This is evidenced by Adam’s lack of sexual experience and his fear of having sex for “obvious reasons” (likely referencing the AIDS epidemic, although not explicitly mentioned). Harry represents the gay men who have been lost and the survivors may feel guilt for not being able to save or comfort them. Harry symbolizes Adam’s longing for intimacy, connection, and pleasure, but I believe more intense ghostly encounters, a grittier tone, and less pessimistic themes could have made it feel more authentic.

The impact is unique.

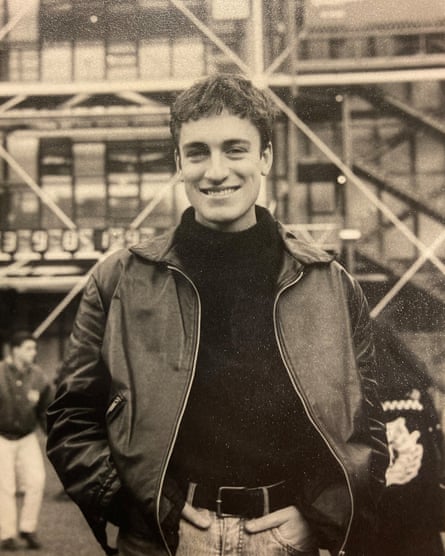

Tim Lusher

Display the image in full screen mode.

During the 1980s, when Adam was a child and I was a teenager, Britain experienced an extraordinary time. The punk movement had shaken up the previous decade, challenging traditional cultural norms and allowing for a new wave of youthful energy. This opened the door for art and fashion students to take center stage, becoming instant pop stars with their unique blend of fancy hats, glittery glamour, pretentious poetry, and scrappy charm. I would sit on large cushions from Habitat in my bedroom in the village, which I had decorated with contrasting browns and furnished with chrome-and-glass coffee tables from Argos, ferns, spotlights, and dimmer switches. I would listen to Trevor Horn’s spacey future-pop on my Akai boombox, including his production of Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s beautiful song “The Power of Love,” which tugs at the heartstrings in All of Us Strangers. I also spent hours reading about the wild tales of London’s club scene in my favorite magazines: Blitz, the Face, and i-D.

The time period was filled with attractive individuals, but also had an unpleasant side. The television, which only had four channels until 1987, presented stories about a terrifying, incurable disease and frightened us with grim health commercials featuring tombstones and icebergs. (We also worried about nuclear war and rabies, but Aids was the top fear.) The people on TV, who you sadly realized were probably similar to you, were all characters in sitcoms and friendly talk show hosts (“confirmed bachelors”) who knew how far they could push the boundaries of risqué humor before losing the delicate tolerance of others and being avoided by them in stores. They were not relatable.

Back in the day, you could only keep in touch with those you were truly close to – your family, neighbors, and schoolmates. You would sit in your house and use a landline to make good old-fashioned phone calls to them. There was no internet, no convenient way to reach out to those beyond your immediate circle and learn about their experiences.

While attending university, I came across a pamphlet discussing the risks associated with sexual activity. I found this in my mailbox, and just to clarify, it was not a euphemism. I chose to ignore the events of freshers week, but many others did not. Some individuals met each other by chance, while others had intentionally planned to do so. A friend of mine recalls that bars would provide paper and pens so people could exchange numbers and arrange a date. He had a seven-step approach for approaching someone he found attractive: pass by them, take seven steps, glance back and smile, walk another seven steps, turn around again, and if they reciprocated the smile, he would go back and initiate conversation. While there were a few individuals who were openly and proudly out, for the most part, it was all just speculation and it was rare to actually see someone who identified as LGBTQ+.

Display the image in full screen mode.

During earlier times, which may seem strange to younger individuals now, before the internet, cell phones, and constant accessibility, being bold and physically present in the world was highly valued. Advertisements in the back pages of magazines, which were printed on paper and either purchased or found in clubs, often contained longing requests for people and moments that had passed by in life. For example, one advertisement read: “Monday at 10am in November on the Northern line. I had brown hair and was wearing a suit and carrying an umbrella. You had blond hair, a leather jacket, and a black cap. We exchanged smiles but didn’t speak. You got off at Goodge Street.”

We are now linked and determined. I viewed All of Us Strangers with a group of men from the Adam generation through a film club. I could detect the sound of sniffles in the theater from young women who could have chosen to watch Mean Girls or Poor Things, but instead witnessed two men portray their love story. Our row appeared moved but did not shed any tears when the lights turned on. Love, desire, isolation, terror, sorrow – these emotions affect us all, but in different ways.

‘A theatrical schema of invented grief and alienation’

Caspar Salmon

The title is jarring, but not because of the word “strangers.” It is a story about complete alienation, but it is the use of “all of us” that is confusing. Who exactly is included in this group? The film focuses solely and intensely on one character, leaving little room for a sense of community. It examines a man who is so consumed by grief that everyone else seems to be a projection of his own mind.

Your enjoyment of All of Us Strangers will heavily rely on your ability to embrace the various levels of artificiality presented to you in rapid succession. Filmmaker Andrew Haigh challenges viewers to temporarily suspend their disbelief and join him on a journey where the main character, Adam, is able to interact with the apparitions of his deceased parents. This aspect requires a certain level of indulgence, as these characters are not fully developed and primarily exist to represent the love that Adam yearns for. The way they readily accept his coming out with exaggerated sincerity may come across as forced and contrived.

The movie also expects the audience to show the same compassion in understanding Harry (Paul Mescal) as a representation of Adam’s id. It also asks us to overlook the artificiality of the situation where Adam, a well-educated gay writer in his forties, is completely alone and without friends in a terrible new housing development in Stratford, similar to a contestant on The Apprentice. As a writer, I find this too difficult to accept and it ultimately causes the entire project to collapse. Instead of a beautifully crafted fever-dream about loss and grief, it becomes an insincere creation where every word feels forced and unearned.

There are certainly challenges that queer men face, such as feelings of isolation, addiction, and their attitudes towards sex. However, Adam and his imagined characters only represent his own experiences, a dramatic portrayal of fabricated sorrow and disconnection, confined within an implausible story.

“In the 1980s, being homosexual and seeking love often resulted in a sense of isolation.”

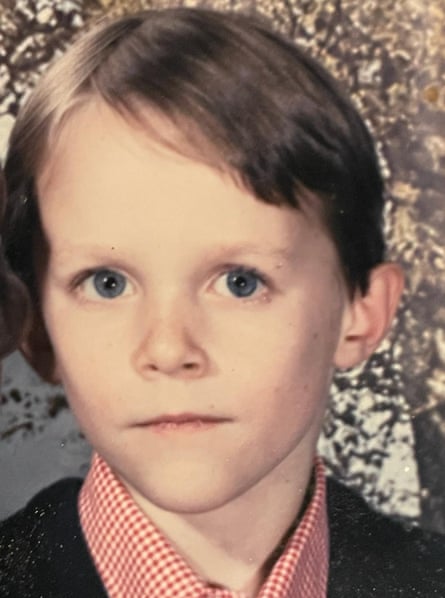

Chris Smith

Display image in full-screen mode.

This is a remarkable, haunting film – beautifully directed and acted – and it takes me right back to all the intensity and struggle of being a young gay man in the 80s, fuelled further by a soundtrack of songs from the period. The exploration of the hesitancy of gay intimacy – with a partner and above all with parents – shows how far we have come since those days.

During the 1980s, being homosexual meant being different from the majority. Individuals had to create their own unique path and relationships, which often led to feelings of isolation. However, this is not the case for many young homosexuals today. While there were still friends to confide in, there was still a part of one’s identity that was challenging to express. If one was fortunate, their family would also be supportive and understanding. But the process of reaching this point was not an easy one.

I was always anxious when it came to confessing to my parents (“Mom, there’s something I’ve been wanting to tell you for a while”). I may have made it worse for myself by also sharing it with the world at the same time. It often involved experiencing fear, isolation, discomfort, and eventually arriving at a place of acceptance: this is the journey Adam embarks on in the movie, with his parents remaining unchanged.

But there’s real intimacy in his parents’ responses, and you even begin to glimpse something beyond acceptance that celebrates Adam’s gayness and the relationship he has now found. Moving from acceptance to celebration is surely the journey we all hope for – and it’s something that now happens (thank goodness) more frequently.

You may have often felt alone in your search for love as a gay person in the 1980s. This is similar to what Adam experiences in the film, as he grows up and finds love with Harry. Finding a sense of security and support in love was something we all strived for, but it wasn’t always easy to come by. However, as Adam eventually receives love and support from his parents and Harry, he feels fulfilled. The contrast between the loneliness of loss and the fulfillment of love is beautifully portrayed in the film. Ultimately, fulfillment is the ultimate goal. This movie is a must-see.

Struggling with an almost excessive desire to make you cry at every available opportunity.

Barry Levitt

All of Us Strangers tries to capture how isolating homosexuality, or indeed any queerness can be, even in a big city that in theory offers more opportunities for queer people than anywhere else. It mostly succeeds in this, but this film seems exclusively interested in gay despair. Haigh’s film wants us to know that queerness and misery are intrinsically linked and lets us know this at every opportunity. Gorgeous, haunting cinematography and great performances can’t make up for a script that hammers the same point ad nauseam.

Adam and Harryare some of the saddest characters I can recall in movies, and while their performances impress, their chemistry together is sorely lacking. The film feels so dreamlike and detached from reality that the central relationship between Adam and Harry never feels genuine. It’s as if the pair only desire each other because they’re both desperately lonely and not because of anything they offer as people.

I was taken aback by the sense of disconnection I experienced while watching the film. Although there is a compelling narrative, All of Us Strangers seems fixated on manipulating emotions and trying to make the audience cry at every opportunity. As a result, the characters are not fully developed and lack the complexity needed for us to become invested in their stories. Adam and Harry come across as empty vessels, defined only by their feelings of isolation and sorrow.

I was particularly disappointed with All of Us Strangers because Haigh is a talented director, having already captured the complexities of gay love and isolation in his film Weekend from 2011. While Weekend had a strong message about the LGBTQ+ experience, All of Us Strangers focuses too much on queer trauma without offering any meaningful resolution.

The concept of love and loss does not discriminate based on age.

Mark O’Connell

Display the image in full screen.

That floral beige kitchen, the Saturday shopping-centre burgers, the Aids ad headstones warning my parents how I might die, the fear that Holly Johnson will out me in my wicker-heavy lounge if I look at him and his leather-clad confidence on Top of the Pops – I too was that doughy, 12-year-old only-child “poof” who could not throw a ball. Idle boomer bias wrapped in an Aids panic was quite the Home Counties starting pistol for a whole swath of us young Adams.

Death and difference were our flash-forwards. It is not just the dusty tinsel, hooped earrings and DayGlo knitwear of Haigh’s queer opus that remind. The tough brilliance of All of Us Strangers is its familiar gut-punch for more than one generation of gay men forced to fear intimacy and love before they even hit their teens.

In the movie, Adam is seen as a loner not because he lost his parents at a young age, but because they never truly understood his identity. This is contrasted by Harry, who is also a loner because his parents do know who he is. Adam’s parents struggle to accept his sexuality and believe that he cannot be both gay and happy. Similarly, a younger version of Harry is shown with his father on a train, resigned to the fact that his happiness may be out of reach. While these two characters are decades apart in the story, their experiences as queer individuals are two sides of the same coin. It is disheartening that our differences are still reinforced, but Haigh shows that we can learn to navigate them better.

In the age of hookup apps, many twenty-something individuals, like Harry, struggle to engage in traditional forms of dating or enjoy carefree activities, such as visiting the Royal Vauxhall Tavern. Adam is hesitant about pursuing sexual relationships and intimacy. Harry only feels comfortable initiating conversation with strangers. As the credits roll and the Frankie Goes to Hollywood song plays, the film All of Us Strangers serves as a universal reminder that love and loss transcend generations.

Source: theguardian.com