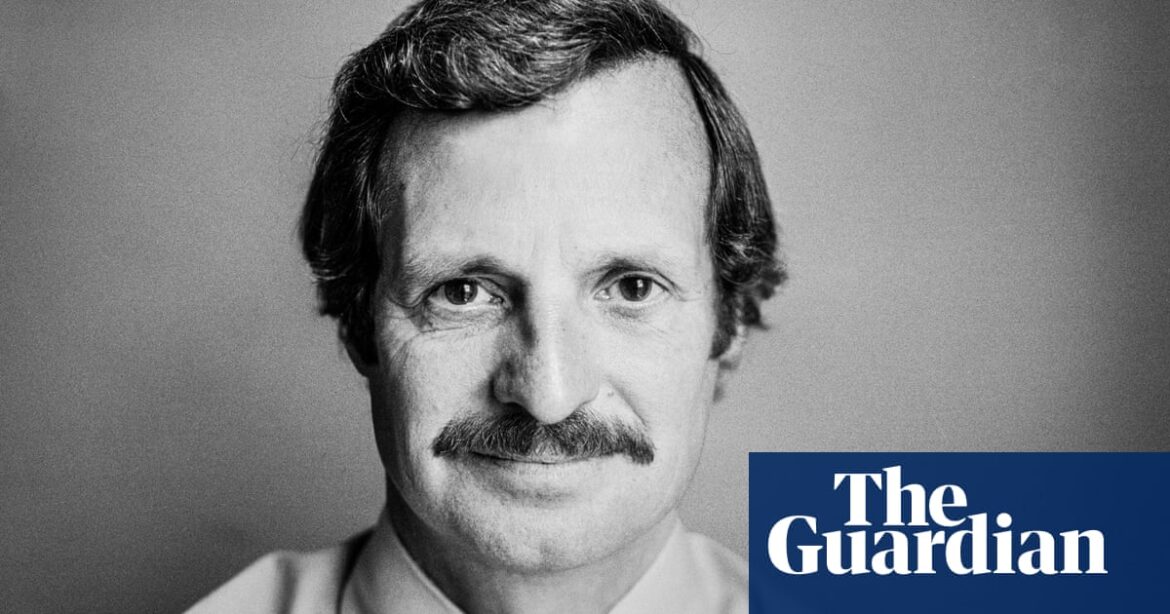

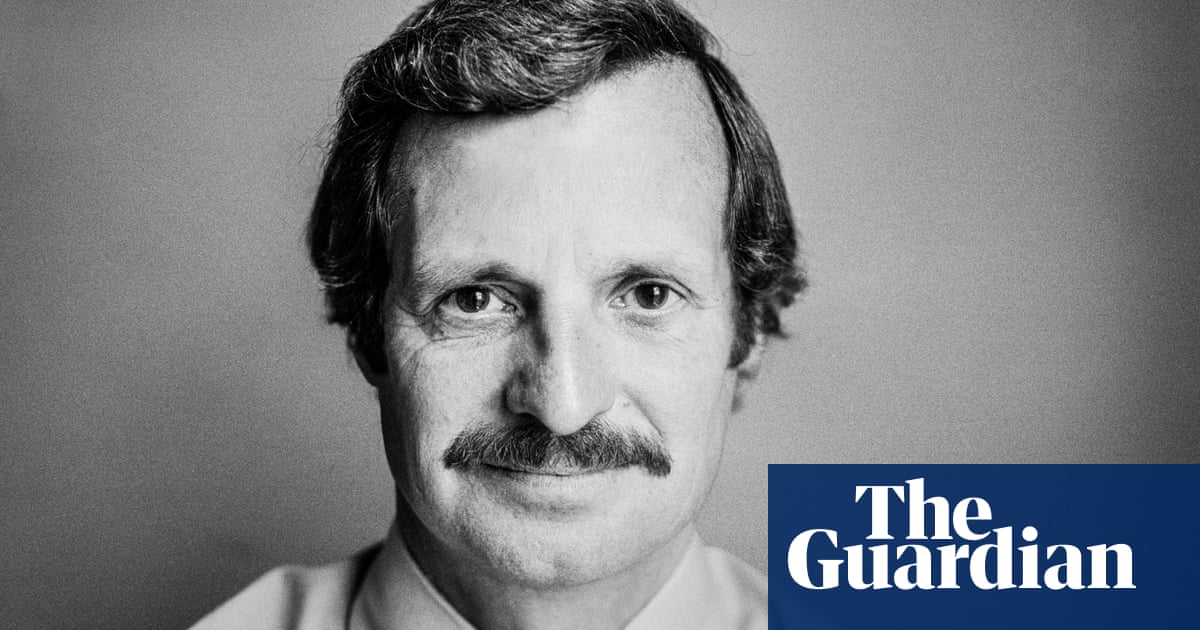

Ronald Atkin, who previously held the position of sports editor at the Observer, was a journalist known for his exceptional standards. He was skilled at both managing the writing of others and creating his own work, particularly in regards to top-level tennis and football events. However, as a member of the traditional Fleet Street newspaper community, he was also able to find humor in the quirks of his profession.

The Sports Journalists’ Association voted him journalist of the year almost 30 years ago, and in 2012 he wrote a humorous piece for their website listing the numerous ways his name had been misspelled throughout his career. Some variations included Atkins, Aitken, Atkinson, and Hatchkin, and he had also been mistakenly called Rod or Tim instead of Ronald. Even the SJA had gotten it wrong in their citation for his supreme award in 1984.

Ron, who passed away at the age of 92, was known for his accuracy and attention to detail. He worked as a tennis correspondent and wrote about football and cricket for various publications including the Observer, Sunday Telegraph, and Independent on Sunday. He also authored books on subjects such as the Mexican Revolution, the Canadian Mounties, the Dunkirk evacuation, and the Dieppe raid of 1942. In addition, he wrote a guide to the top bars in the world, which reflected his friendly and sociable personality, a common trait among journalists from the former Fleet Street.

In 1982, two years following the passing of his initial spouse Brenda, he wed Julie Welch. She was a colleague at the Observer and he had supported her to become the first female reporter to cover English league football for a major newspaper. During her early days in the press box, Welch faced discrimination and harassment, including being forcibly kissed by the manager of Stoke City, Tony Waddington.

As the head of her department, Atkin promptly reached out to Waddington. She initially requested a resolution to the recurring issue of obtaining passes for Stoke’s games. She also requested that he refrain from kissing our reporters until this matter is resolved.

He was born in Aspley, a neighborhood in Nottingham, where his parents held jobs in significant local businesses. His father, George, was employed at Raleigh, which was the biggest cycle factory in the world at the time, while his mother, Winnie (formerly Truman), was a lacemaker. He went to High Pavement grammar school before leaving at 16 to work for the Nottingham Evening Post, one of the four daily newspapers in the city.

He followed the traditional path of those demonstrating talent and passion, moving from messenger to copy assistant to journalist and assistant editor.

In 1953, he came to Bermuda for the first time to work as a journalist for a local newspaper. When he returned to the UK four years later, he took on occasional editing jobs on Fleet Street and got married to Brenda Burton, who was a neighbor in Aspley. Two of her sculptures were selected for the summer exhibition at the Royal Academy. After their first son, Tim, was born, the family went back to Bermuda for a few more years before eventually moving back to Britain with their second son, Mike. Ron then secured a position as an editor at the Daily Mail.

Saturday subbing shifts on the Observer’s sports desk led to the offer of a position as deputy to the sports editor, Clifford Makins, working with such star writers as Hugh McIlvanney and Arthur Hopcraft, who became his great friends. There was also the opportunity to contribute the occasional match report until he was promoted to sports editor after Makins’ departure in 1972.

He started writing books, focusing mainly on military history. His book about the Mexican revolution from 1910-1920 was well-received and allowed him to purchase a house in Spain’s Costa Brava, which became a regular vacation spot for his family.

In 1975, Donald Trelford, the editor of The Observer, made the decision for a modification. Ron was given the option to choose from various writing positions and ultimately chose to be the tennis correspondent, focusing on a sport he was passionate about. This role allowed him to travel to major tournaments in New York, Paris, Melbourne, and Wimbledon, bringing him joy and forming many new friendships over the following decades. He also had the chance to ghostwrite the memoir of Fred Perry, a renowned Wimbledon champion from before World War II.

During a time when reporters and their subjects would often share accommodations and meals, Arthur Ashe, the winner of the 1975 Wimbledon tournament, became the godfather to Ron’s fourth child, Nick. Ron’s third son, Lucas, had already been given a famous godfather in Brian Clough, the renowned manager of Nottingham Forest, the team that Ron supported until his passing.

On Saturdays without tennis to report on, he would attend football or cricket games, showcasing his diverse interest in sports.

During his vacation in France in 1994, he discovered that his position at the Observer was being terminated. He had already been offered the role of tennis correspondent at the Sunday Telegraph and was content to accept the severance package and the new job. In 2000, he moved once again to the Independent on Sunday, where he spent many years as part of a cheerful team, covering tennis, football, and other sports. However, this also came to an end in 2008.

Into his 80s, he persisted in jotting down daily entries for the Wimbledon programme, indulging in his passion for music (he even got the opportunity to attend a Frank Sinatra concert at Carnegie Hall while visiting New York for the US Open), and immersing himself in the works of his beloved authors such as Paul Theroux, Garrison Keillor, and Robert Harris.

Julie, author of The Fleet Street Girls (published in 2020), and his four sons from both marriages, survive him.