“It’s a bit like three-dimensional chess, and it’s much more intellectual than an average sport because it’s so complicated,” Maggie Henderson-Tew says through a wide grin after walking off the court.

Amid an explosion of interest in newfangled racket sports such as pickleball and padel, which have found popularity due to their dynamic, speedy and easy to learn styles of play, one Sydney sports club is instead leaning into the past – specifically, the Tudor period.

This week, Sydney became home to Australia’s fourth court for “real tennis” – also known as royal tennis – the precursor sport to what would evolve to be modern-day tennis (or “lawn tennis”) and squash.

Unlike the low barriers to entry that have seen pickleball and padel gain broad appeal, real tennis’s attraction is in its quirks of tradition, cumbersome equipment and labyrinthine scoring system.

“People get absolutely fanatically into it, but it’s incredibly frustrating when you start out until you hit your first good shot, then it feels phenomenal,” says Henderson-Tew.

-

Sign up for a weekly email featuring our best reads

“If you can hit one in every 20 balls your first time playing that’s a very good sign. You have to get down low like handball because the ball doesn’t really bounce,” she says.

‘It takes two years of playing to be hopeless’

While initially known as jeu de paume – French for “palm game” – real tennis has progressed to be played with rackets, albeit ones with an offset head to mimic the angle of an outstretched hand.

“A racket is essentially an arm on a stick, with a tiny sweet spot,” Henderson-Tew says. These days, just one company, Grays, produces rackets for the sport, in a side operation it’s understood to not make a profit from.

Despite the game continuing to be played through to the present day in the UK, US, Australia and France – Sydney’s new court is just the world’s 50th – competition rackets are made of wood, and can feel closer to a cricket bat than a state-of-the-art lawn tennis racket.

Asymmetry in real tennis extends far beyond its rackets.

Courts, which are rectangular and built with roofs, include sloped sections on three of the four walls – the sport itself was spun out of how handball would be played in courtyards and streets in medieval times, and some say the slopes are inspired by what would have been awnings covering shops.

Every point must begin by serving the ball on to a specific slope – or “penthouse” as it is known – while the loud thud of a ball landing on one of the slopes before bouncing down closely resembles the soundscape of a bowling alley.

There are also various netted “openings” around the court, spread asymmetrically around the walls, whose functions are similar to activating a mini-game on a lifesize pinball machine.

Hitting the ball in some of the openings is one way to win a point outright. However, if a serving player slightly mis-hits the ball into a different adjacent opening, they can lose serve mid-game and trigger a change of ends. Such an occurrence leads to what is called a “chase”, which must be resolved through play from a range of dozens of different fixed positions on the court.

The scoring system might be the most striking resemblance to the sport played at the Australian Open or Wimbledon, in that games are run to a love-15-30-40 score.

But that’s where the similarities end. Points are won by hitting winning openings or if an opponent sends a ball into the drooping net. A double bounce does not mean a lost point. Tournament matches can be played to as many as the best of 13 sets over three days.

Both singles and doubles competitions are played, but “triples” games have been discontinued, now considered too dangerous. The world’s best professionals compete at the top level into their 50s.

The convoluted rules and difficulty of play are poked fun at by many at Sydney’s new club.

“It takes two years of playing to be hopeless,” jokes Chris Ronaldson, a former world champion of the sport.

after newsletter promotion

He and his wife, Henderson-Tew, moved from Radley College, a school in Oxfordshire in the UK where they helmed a real tennis court, to Sydney six months ago to help prepare the club.

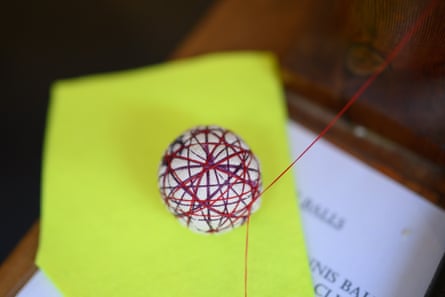

Ronaldson was tasked with one of the sport’s more bizarre tasks. Balls for real tennis are not mass produced. Instead, each clubhouse must make them individually by hand by wrapping cork in cotton webbing before sewing them up in yellow cloth.

Since arriving in Sydney, Ronaldson, now 75, has made about 300 balls, mostly from his garage while waiting for the court’s to be completed. Each one takes him about 40 minutes.

New court for an old sport

For decades, the Sydney Real Tennis Club has been a nomadic group, travelling to courts in Melbourne, Hobart and Ballarat. In the late 1990s, a court was built at Sydney’s Macquarie University, but this proved unpopular among students and disagreements between the club and university management saw it turned into a childcare centre after seven years.

The club spent years searching for a new base and lobbying for support, ultimately settling on the Cheltenham Recreation Club, on Sydney’s leafy north shore, as the premises to build its new court.

The success of the campaign was largely due to a New South Wales government grant. At the club’s official opening ceremony on Monday, former local MP and premier Dominic Perrottet was acknowledged for his role in securing the $1.4m grant for construction – an impressive amount of public money for a sports club with roughly 30 registered players.

Now, after 20 years in the wilderness, as of this week Sydney has once again hosted competitive real tennis, with players from Britain and the United States joining contestants from interstate who travelled to Cheltenham for the inaugural Bilby competition.

Chris Cooper, the club’s secretary, says initial interest from the community has been strong, with a steady stream of private bookings from first-timers as well as others “coming out of the woodworks” who had played in the past.

“Percentage wise it’s one of the fastest growing sports in the country,” he jokes.

Attracting the levels of traction that pickleball has come to enjoy may prove ambitious, though, given the sport’s complexity and obscurity.

Ronaldson is enthusiastic about his sport’s latest venue, but encourages new players not to be dissuaded by the initial difficulty of learning how to hit what are much heavier balls, less bouncy with even heavier rackets.

In addition to players having to adapt to subtleties in an away club’s homemade balls, the dimensions and designs of actual courts also vary slightly – no two courts are the same.

“We’ve designed our court with a few little idiosyncrasies that give us a home advantage,” Cooper says. That includes a protrusion of one the court’s walls that slopes at a steeper angle.

With the club now up and running, Ronaldson and Henderson-Tew will return to the UK. Taking over as the club’s resident professional is Alex Marino-Hume.

The 29-year-old – a former choral singer who performed at King Charles’s coronation – joins from the real tennis club at Lord’s in London, and has relocated here with his wife, Charlotte, for four years. Managing the club will be his full-time profession.

At this week’s tournament, most players have so far skewed older and male. Despite its royal associations, Marino-Hume is aiming to make the club inclusive, and is hoping to see many women and children take it up.

“It’s not elite, it started in the streets,” Marino-Hume says.

Charlotte is starting out with modest goals – like finding a competent hitting partner.

“When you can find someone to play who is able to actually return a shot it’s quite satisfying.”