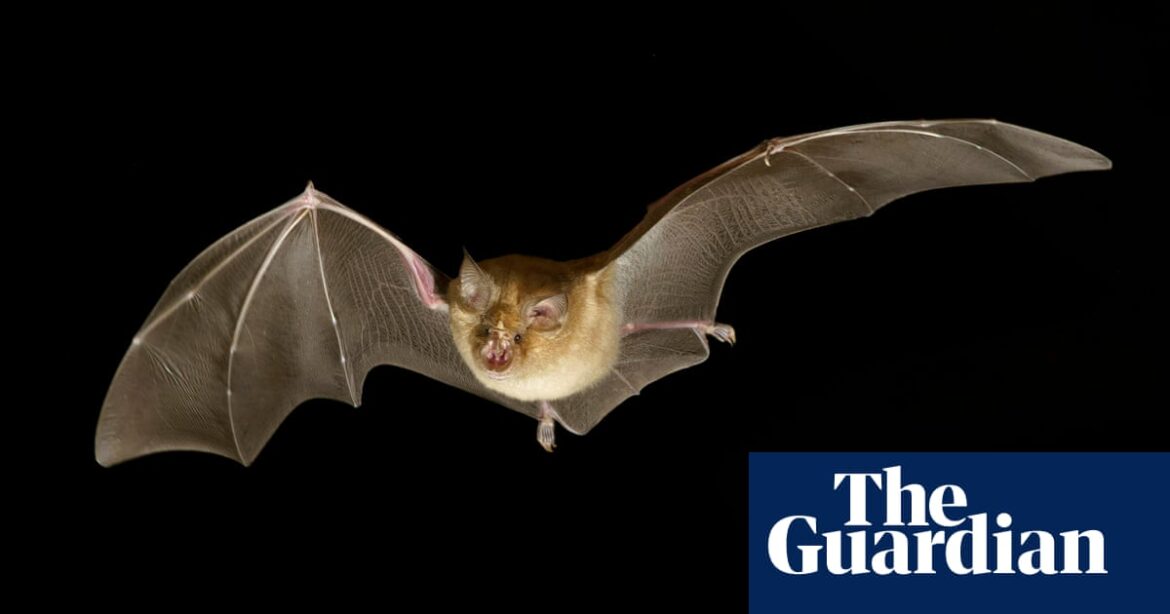

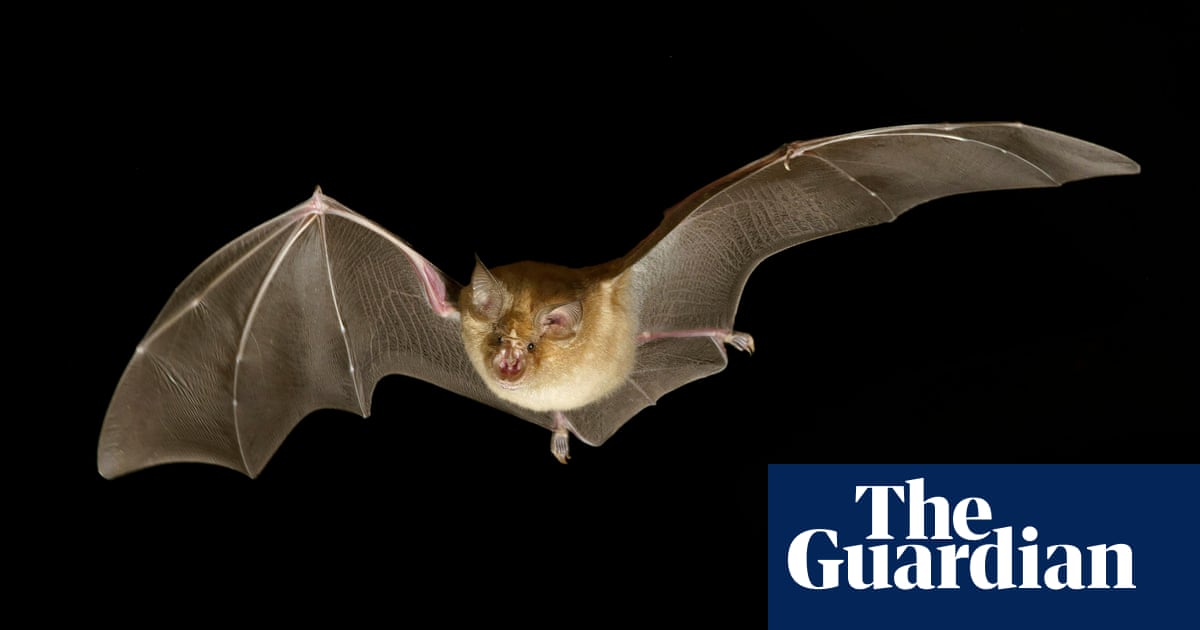

Researchers have discovered that bats return to their roosts in a “leapfrogging” pattern after a night of hunting, which helps them make the most of their time out and avoid predators.

A group of researchers from Cardiff University and the University of Sussex created a mathematical representation using “trajectory data” to monitor the movement of greater horseshoe bats in Devon, in order to determine how they interact with their surroundings during the night.

The researchers discovered that after leaving their homes, which are usually caves or lofts, the bats disperse in a one-mile radius for the first hour and a half to two hours before slowly returning home.

Scientists observed that the bat which was farthest away did not seem interested in staying at the edge, and instead jumped over the nearest bat on its way back to the roost.

Thomas Woolley, a senior lecturer at the school of mathematics at Cardiff University and lead author of the study, noted that the bat furthest from the roost did not seem to intentionally choose its position. This resulted in a chain reaction of motion as the furthest bat hopped back towards the roost.

The team’s research, published in the Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, proposes that the bat furthest from the group would recognize its vulnerability to predators and begin to return. The following bat in the group would also take this action, and so on. According to the paper, a bat would be able to determine that it was the furthest from the group if it did not detect calls coming from all directions.

Before, it was believed that the “core sustenance zone” (the area where most foraging takes place) had a radius of 2km (1.25 miles). However, the team’s model indicates that it is slightly smaller at 1.8km.

Fiona Mathews, a professor of environmental biology at the University of Sussex, collaborated with a team of ecologists and volunteers to collect the trajectory data of bats. The bats were captured in a humane manner and had small radio transmitters attached to their backs to track their flight patterns.

Mathews explained that the greater horseshoe bat population in Europe is at risk. While efforts have been made to safeguard their roosts, there is still limited knowledge on how to preserve their hunting grounds due to the difficulty of tracking these swift creatures in low light conditions. In fact, they are capable of surpassing the speed of a car on a rural road.

Bats, similar to bees, ants, rooks, and penguins, have a tendency to gather closely while resting. However, in order to prevent competition among themselves, they must spread out from this spot to find food.

“Having the ability to simulate their nightly movements will aid in preserving their feeding areas. Furthermore, it will provide insight into how they may repopulate regions where they have previously disappeared, such as the south-east of England.”

The article acknowledges that there are constraints to its findings. Bats do not consistently return to the same location for rest, thus further research is needed to expand the results to encompass various roosting sites. Different bat species may have varying behaviors, and even within the same species, flight patterns can differ during specific seasons.

Source: theguardian.com