One of the oldest indie labels in Britain sits down a muddy lane on an old RAF site, less than a mile from the sea, half an hour from the mountains of Eryri. Founded in 1969, Sain – meaning sound in Welsh, pronounced (in English) like “sign” – is an unusual label, host to a remarkable treasure trove of music. And now it is on a drive to explore its past, present and future.

It has recently launched a new anthology series, Stafell Sbâr Sain (Sain’s Spare Room), which gets up-and-coming Welsh musicians to record in its vintage analogue studio. Tyrchu Sain (Digging Sain) is a new album by Don Leisure (AKA producer Aly Jamal) which remixes the label’s 56-year-old catalogue into mesmerising new shapes. Meanwhile the label’s archive of Welsh-language music – more than 3,000 albums of pop, psych, prog, punk, funk, folk, opera, choral music and other genres on vinyl and cassette – is being digitised, so it can be released on streaming services for the first time and archived in the National Library of Wales.

I visit the HQ outside the village of Llandwrog in Gwynedd with Kev Tame as my tour guide. A former member of electronic collective Acid Casuals and rock band Big Leaves (who were signed to Sain’s 80s-00s pop imprint Crai, which also released early singles by Catatonia), he is part of a generation who are keen to preserve and revive Welsh music history. He runs the Welsh music prize with 6 Music DJ Huw Stephens, and leads the Sain archive and development project.

“Sain is a very unofficial institution in terms of Welsh music – like an annoying younger sister or brother to others that exist, like BBC Radio Cymru and S4C,” he says. The HQ is a quirky place. Past its purple-painted reception run by the formidable Rhian Eleri, artworks from the label’s 2019 50th birthday celebrations line its corridors, using Sain’s early DIY collage aesthetic as inspiration, with the work of musician and poet Geraint Jarman (who died this week) who mixed rock, reggae and pop and played with Welsh poetic forms, being especially prominent. That frisky, hands-on creativity crackles elsewhere.

It’s there in the huge, modernist studio built in the space of the demolished RAF lorry garage and decorated in stone and wood. (Before 1980, Sain was based in a nearby factory canteen and a cowshed, having begun life in a Cardiff front room.) “The stones apparently came from the farm down the road in a wheelbarrow,” says Aled Wyn Hughes, one of the studio’s three managers, who is today producing the lush debut single by new bilingual country artist Martha. (Hughes also plays in the acclaimed folk-rock band Cowbois Rhos Botwnnog.)

Folk musician and researcher Gwenan Gibbard works here, too, helping to administer the digitisation of the archive, a project which is funded by Arfor, a partnership between the Welsh government, Plaid Cymru and North Walian councils to protect and promote the Welsh language. “Even going back to the 1960s, people were making music in every genre in Welsh,” she points out. “Which didn’t always happen in some other minority languages, like Gaelic.” A touring culture based around clubs, miners’ institutes and local theatres has helped, as has the popularity of regional and national eisteddfod festivals, which still thrive today.

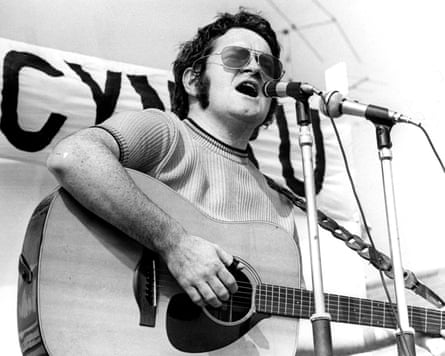

Sain’s roots are political. In 1969, Dafydd Iwan had just released Carlo, a single satirising that summer’s investiture of the new Prince of Wales, on an older Welsh-language label, Welsh Teldisc. But he was frustrated by the lack of access to quality recording studios or equipment in Wales. He co-founded Sain with protest singer Huw Jones, who released the first single on the label later that year: the fabulous, soulful Dŵr, about a man returning to his village to find it flooded, echoing the fate of Capel Celyn, which was flooded in 1965 to make a reservoir for Liverpool.

Now 81, Iwan lives only 10 minutes from Sain, near Caernarfon. He has become well known again in Wales in recent years since his 1983 song Yma O Hyd (Still Here), famously sung on the picket lines during the miners’ strike, was adopted by the Wales football team, and covered by bilingual drill artist Sage Todz for the 2022 World Cup.

He reflects on global politics at the time he founded the label: “Civil rights, the student riots on the continent, the campaigns against the Vietnam war – we got this feeling that the world had to change, and that feeling translated into our peculiar situation in Wales.” The 1967 Welsh Language Act had allowed Welsh to be used in legal proceedings again, for the first time since the 16th century, and Iwan and his friends were driven to make it “a fully modern language”, he says. “That meant doing everything in Welsh – theatre, films, recording albums. Unlike now, there was very little Welsh on television and radio, and the recording industry in our country was a pretty amateur affair. Sain grew out of that era – of thinking we should get things moving.”

Co-founder Jones ensured Sain’s early success, Iwan says. “He was a pretty screwed-on kind of chap. He never risked anything. We got to the beginning of the 80s, when we bought the RAF mess and built a good studio, by just selling records and saving money.” Iwan sees Sain’s mission now as “co-working” with others, he says, including on a very local level. They are opening a co-working space within the headquarters this month, and collaborating on a community pub and music venue project in the village in which they’ve been based for over half a century.

Iwan is also delighted with Aly Jamal’s “very exciting” Tyrchu Sain remix album. Iwan performs on its last track, Diolch a Nos Da (Thank You and Good Night), during which he thanks, inclusively, “all who have been a part of creating the exciting world of Welsh music, yn Gymraeg [in Welsh], in English, and other languages”. He ends the track like a Celtic Sun Ra: “Together in creativity for peace!”

Jamal loved meeting Iwan, too, he says, when we chat two days later in Cardiff. “Dafydd’s a super sharp guy – very welcoming about what Welsh culture is, and what it could be.” Jamal’s introduction to Sain were its tracks on the 2006 compilation Welsh Rare Beat, put together by Gruff Rhys, Andy Votel and others for Finders Keepers Records. It featured acid-folk-flavoured female groups Sidan and Y Diliau, and twisted, funky tracks by Meic Stevens and rock band Brân. “It felt like outsider music to me in the same way as old Turkish psych.” Jamal says.

This music’s roots in the Welsh language shook him. He was taught Welsh at primary and secondary school – but it had a “real afterthought vibe to it, like it wasn’t that important”. Hearing the language in this musical context also made him consider his Welsh identity alongside his family’s roots in India and east Africa. “Wales was the first colony of the British empire. It made me think about the efforts the powers that be go to, to dilute other languages and cultures.”

While digging, Jamal fell in love with the music of Delwyn Sion, and since finding out that he was from Aberdare, too they’ve become friends. Jamal sampled Sion’s track Aros yn Dy Gwmni (Stay in Your Company) for a single, Tyrchu, that features Gruff Rhys on vocals. Another track, Tad a Mab (Father and Son), mixes the drum playing of a friend, Dafydd Brynmor Davies, with the music of his late father, John Davies, who played with rock band Eliffant. “That was really special,” says Jamal. Elsewhere on the album contemporary artists such as the tropicalia-loving Carwyn Ellis, indie band Boy Azooga and jazz harpist Amanda Whiting inventively connect Wales’s past and present.

It astonishes Iwan how differently the Welsh language is thought of now. “The attitude towards it has changed completely,” he says. “All the political parties in the Senedd are for the language, to various degrees, so the Welsh language is no longer a political issue in terms of its status. There’s always a danger of sliding away from the language, because of all the English influences – but that’s the same in all small countries.”

Jamal says he was moved to see Iwan’s reaction to his album on an episode of the S4C arts show, Curadur (Curator, available on BBC iPlayer with subtitles). “He was really teary-eyed. He appreciates the fact that it’s not just the music we’re celebrating, but the politics of expression and pride in the language and culture. It’s cool for him. It’s cool for all of us.”

Source: theguardian.com