Given that he is the producer behind some of the most cherished and idiosyncratic British pop of the 1980s, from Elvis Costello to Dexys Midnight Runners and the Teardrop Explodes, Clive Langer sounds surprisingly bad at predicting what will do well. “I was invited to possibly work with Madonna, around the time of Holiday,” he remembers. “I went to see her at the Music Machine and I just didn’t get it. I still don’t get it.” So he turned her down. And when Dexys laid down Come on Eileen with Langer behind the mixing desk, he didn’t think it would be a hit. “I was completely wrong. I never had the faith.”

It duly reached No 1 and became the biggest-selling single of 1982, just one of the many triumphs Langer had with production partner Alan Winstanley. Together they shaped a generation of British pop with David Bowie, Mick Jagger and Lloyd Cole, plus eight full albums with Madness across five decades.

He also dabbled with his own bands, and is now a frontman at the age of 70 in the Clang Group, whose second album of sharp guitar pop, New Clang, is out next month. It reflects a “compulsion to write songs, express myself and turn it up a bit louder,” Langer says over a cup of tea at his home in Hackney, London.

He knows he’s lucky to have done any of it. His Polish father, who was Jewish, fled the Nazis – “They told him, ‘Go right …’ He took a left and never saw his parents or his brother again,” – later making it to the UK and joining the RAF, where he met Langer’s mother. Langer’s childhood in London put him at the centre of “an incredible time for music. I dropped acid aged 13 and saw Cream, Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin in a pub called Klooks Kleek. We didn’t have tickets to Janis Joplin at the Albert Hall, but we figured that if six of us tried to run in, four of us would make it – and we did.”

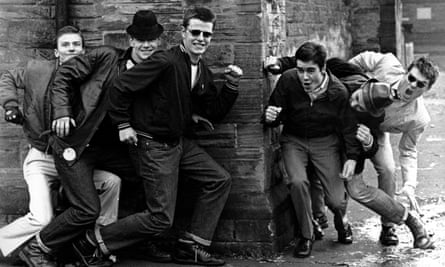

Langer left for art school in Canterbury, where Ian Dury was a teacher. He formed his first band, Deaf School, at Liverpool School of Art in 1974, inspired by Dury’s pre-Blockheads band Kilburn and the High Roads. “We were very theatrical characters. A bit Sparks, a bit Roxy.” After punk arrived, “we lost all momentum”, but they had amassed a range of famous admirers: the likes of Julian Cope, Suggs, Pete Burns and Steve Strange. “Kevin Rowland came into our dressing room in Birmingham before starting Dexys Midnight Runners. Then Big In Japan started from our road crew and included Bill Drummond who formed the KLF, Holly Johnson who started Frankie Goes to Hollywood and Ian Broudie who became Lightning Seeds. I joined [as guitarist] and some of the others went on to be in the Teardrop Explodes or Siouxsie and the Banshees.”

In Deaf School, Langer had paid close attention to the band’s producers, and remembered their techniques when teenage Deaf School fans North London Invaders asked him to record them just as they changed their name to Madness. “I was very nervous when I went in to their rehearsal room clutching a four-pack of beer,” he admits, “but as soon as I heard My Girl I knew this was very special. From then on every record was a hit. They were ambitious and sort of naughty. The studio petty cash might suddenly disappear and if there was any booze about it would soon be gone.”

For the nutty boys’ 1979 debut album, One Step Beyond, Langer teamed up with more experienced engineer Winstanley, soon establishing a way of working where Winstanley handled the technical side while Langer would “rehearse with the bands, sort out the songwriting and arrangements and have an overview. You know, ‘Do we need a trumpet?’”

The wonderfully berserk trumpet solo on the Teardrop Explodes’ 1981 smash Reward was recorded when “there was a lot of acid in the band. So once it kicked in Julian [Cope] spent four hours disagreeing about a guitar chord.” The recording of Dexys’ second album Too-Rye-Ay was just as colourful, with the band “wearing all the clothes and doing the moves like it was a gig. I felt as if I was being pinned to the wall of the rehearsal room. It was that powerful.”

Langer wrote the music himself for another classic, Shipbuilding, a Falklands-era hit for Robert Wyatt later recorded by Elvis Costello, who wrote the lyrics. “I’d tried to write something beautiful for Robert, but myself and various friends all tried to come up with lyrics for it and they were rubbish,” he says. “I bumped into Elvis at a party and a few days later he had the words.”

Langer and Winstanley worked quickly. “Once, we were in the same studio as Trevor Horn and we’d done Elvis’s whole Goodbye Cruel World album in the three weeks Trevor spent on the snare sound for [Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s] Two Tribes.” Simplicity aside, he doesn’t feel they had any particular Midas touch. “Our job was to give record companies hit records and we were just rolling with it. Sometimes you’d be a bit pissed and get talked into it.”

Morrissey was another client, and “working with him was brilliant, because he didn’t write his own music, so I could either co-write the songs [including November Spawned a Monster] or shape them. But he would invite guests to the studio then disappear to his room. I’d have to look after them, thinking, ‘Who are these people?’”

Langer’s career zenith was producing Bowie and Jagger’s No 1 single Dancing in the Street and the former’s No 2 classic Absolute Beginners on the same day in 1985. “They were good friends, but Bowie ran the show and was always looking after Mick. ‘Everything all right, Mick?’ For Absolute Beginners, Bowie did the vocal in one take. He said, ‘There’s one line I can do better.’ We re-did that and the record was finished. He sounded utterly majestic. We hung out. Skiing. New Year’s Eve. With other people, he was always performing, but sometimes I’d get him for an hour or so and we’d just drink and talk. He was so intelligent, funny, knew what he was doing. After that I thought, ‘Where do I go next?’”

In the 90s, Langer and Winstanley mortgaged themselves to the skies turning Hook End Manor, purchased from David Gilmour, into the best equipped studio in Europe. Then, Bush’s 1994 album Sixteen Stone shipped 6m copies in the US. “It was Nirvana lite, but 14-year-old girls absolutely loved them. It paid off all my mortgages.”

After later working with Blur, Catatonia and a-ha, and “spending more time together than with our families”, the duo’s last full album production together was Madness’s 2009 The Liberty of Norton Folgate. Langer also joined a reformed Deaf School but drifted further into alcohol, which he candidly confronts in songs on New Clang.

“I’d always liked a drink at 6pm to listen and reappraise everything with alcohol in me,” he says. “Bottle of wine by the mixing desk – not too close in case you knock it over and fuck everything up. The problem is it’s progressive, then it kills you. After I stopped working I got myself into a right pickle needing a vodka in my coffee at 11am just to feel normal. So I went to see someone for help.”

Now three years sober, Langer is throwing his new energy into the Clang Group. “I don’t sit around thinking about what ifs but there’s a tiny regret that I didn’t do Foo Fighters’ second album,” he admits. “I was flown to the Capitol building in Los Angeles to meet Dave Grohl, but then I suggested that he should play drums on the record instead of the drummer they had then,” he reveals. “I walked out knowing that I’d blown it, but I don’t regret what I said.” This time, however, his instincts were correct: when The Colour and the Shape went double platinum he noticed that the drummer on all but two tracks was Grohl.

Source: theguardian.com