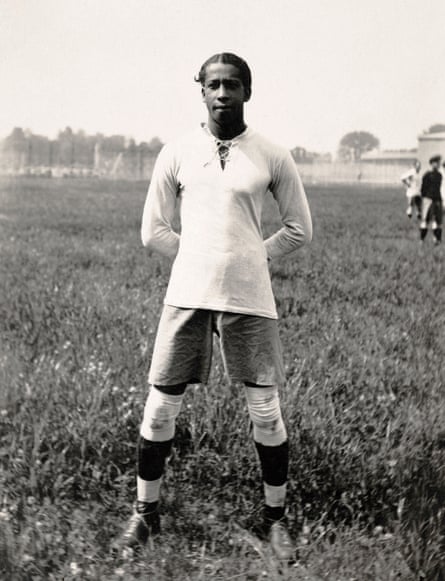

In June 1924, L’Auto, the French sportspaper that had launched the Tour de France, ran a large portrait on its front page. This was the Olympic Games of the Finnish runner Paavo Nurmi and his five gold medals; of Harold Abraham and Eric Liddell, whose story would be told in Chariots of Fire; of Johnny Weissmuller, who would later play Tarzan, winning three swimming golds; of WB Yeats’s brother, Jack, winning Ireland’s first ever medal, in the painting that formed part of the culture programme of that era; but the face of the 1924 Paris Games was the Uruguay centre-half José Andrade.

This was remarkable for two reasons. First because this was the first football tournament to feature countries from Europe and the Americas, a combination that made it the most popular and profitable sport at the Games. And second because Andrade was black. The 1924 Olympics was the Games in which DeHart Hubbard became the first African-American to win gold, in the long jump, but it also gave football its first black superstar, its first global superstar.

Andrade was clearly a player of immense talent. He is one of only four who played for Uruguay in the finals of the 1924 and 1928 Olympics and the 1930 World Cup. Sober historians will point out that the best player was probably the inside-forward Héctor Scarone, while the leader was the right-back José Nasazzi, who always wore a homemade white knitted cap.

But it was Andrade, charismatic and good-looking, who captured the Parisian imagination. His race, as the accompanying text in L’Auto made clear, was a major part of that: the caption described him as “the marvellous and black half-back”.

He was quick and athletic, and was noted for la tijera, a scissoring way he would play the ball while grounded, but he seems to have dominated games less by physicality than by his understanding of space and angles.

When the novelist Colette was dispatched to the Uruguay base in Argenteuil in northern Paris to speak to the team, it was Andrade she really wanted. She watched the team celebrate with an Argentinian band, with Andrade, a gifted carnival musician, joining in on the drums. “Uruguayans,” Colette wrote in Le Matin, “are a strange combination of civilisation and barbarism. Dancing the tango they are wonderful, sublime, better than the best gigolo. But they also dance African cannibal dances that make you shiver.”

That’s not a description that lands comfortably in the modern consciousness, but it was characteristic of the time. To the Parisian intelligentsia, Andrade was the embodiment of primitive modernism, to which, thanks to Picasso, Apollinaire and Stravinsky, they were in thrall.

He was dubbed the Black Pearl and it was inevitable that he would meet up with the person in Paris at the time who shared the nickname, the jazz singer Josephine Baker, whose greatest fame would come a couple of years later with the danse sauvage, performed in just strategically arranged necklaces and a skirt made of 16 bananas. They danced a tango together; whether their relationship went further was a matter of speculation.

And there was plenty of that. Andrade clearly relished the attention. Even if many of the stories about him were exaggerated, he enjoyed a vibrant social life and by the end of the tournament was dressing as a dandy in leather boots, yellow gloves, a silk cravat and a top hat.

Uruguay had entered the Olympic football only on the whim of their government’s minister plenipotentiary in Switzerland, Eduardo Buero, who had been dispatched to a Fifa congress in Geneva the previous year to sign up to the global body as part of a power struggle between two rival football federations in Montevideo.

They were the only South American entrants but the USA sent a team and so too did Egypt, who sprung a major shock by beating Hungary 3-0 in the second round. So appalled were the Hungarians that their government launched an official inquiry, the interviews for which remain in the official archives.

after newsletter promotion

They tell a fascinating story of players frustrated by poor leadership, poor conditions and each other. Some complaints boil down to little more than a dislike of French food – the forward Csibi Braun spoke of meagre breakfasts of “coffee and bread and butter” and “half-raw bloody meat for lunch” – but the Montmartre hotel in which the players were billeted had been selected more for the socialising of officials than the comfort of players.

Things got so bad that the extrovert centre-half Béla Guttmann led the players on a rat hunt, tying their prey by the tails to the doorhandles of officials’ rooms; he never played for his country again, although, after being detained for being Jewish during the second world war and escaping a forced labour camp, he did go on to manage Benfica to two European Cups.

The Irish Free State reached the quarter-final, while the only British involvement was on the benches, with five teams boasting English or Scottish coaches. It was one of them, Switzerland, led by the former Manchester United centre-half Teddy Duckworth – aided by Fred Pentland, who had helped write the first ever coaching manual while interned at Ruhleben during the first world war and would go on to win two league titles and five Copas del Rey with Athletic Club – who faced Uruguay in the final.

Uruguay were far too good, winning 3-0. The former France international Gabriel Hanot, later a leading figure at L’Équipe, described them as “Arab thoroughbreds” as opposed to the “farmhorses” of English football, arguing they would have won even if British teams had competed. Contemporary descriptions, plus the small amount of footage that survives from the 1930 World Cup final, suggests a surprisingly modern style of play, based around short passes and the intermovement of players, despite often dreadful pitches. They can be regarded as the first modern team and that Olympics 100 years ago as the first modern football tournament.

Andrade, meanwhile, was the first modern superstar. Although he played in all three finals, 1924 was his peak. By 1930 he was suffering from syphilis and would soon lose the sight in one eye. He died, impoverished and racked by illness, in an asylum at the age of 55. But in Paris, he had opened up to an enthralled audience a world of possibility.

Source: theguardian.com